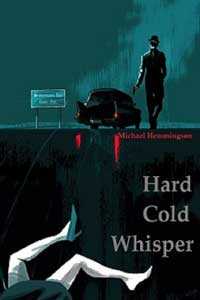

EXTRACT FOR

Hard Cold Whisper

(Michael Hemmingson)

|

Gabriella was cold and calculating—yet I knew that

she was also scared because she told me so. She was doing a good job hiding it;

she would've made an excellent poker player. Or chess champion, the mathematics

of manipulation doing overtime, as each move on her part built up to the grand

scheme of things. I admired her ability to do this and found myself wishing my

own blood could run with such ice in it. And there the two of us stood: in her aunt’s

bedroom, gazing on our intended victim; the old woman lightly snoring, mumbling

something now and then. I wondered about her dreams. I wondered about the curse

she apparently put on me, and would her death cancel it? Gabriella handed me a thick down feather pillow. I

thought about that trick question: What’s heavier, a pound of rocks or a pound

of feathers? “I have to do it?” “I don’t think I can,” she said. She was the brain; I was the muscle. I was up to me. Gabriella’s task was to turn her

aunt over so the woman was on her back. I wanted to suggest that perhaps she

her adenoids would close up and that’d do the job for us, since that was going

to be the explanation for her death. Would it still be murder? I imagine the

D.A.’s office would attempt to argue that . . . if they suspected foul play. “Do it,” said the girl I had fallen in love with.

“Three million dollars, baby,” Gabriella reminded me with a hard cold whisper. And so I did it. It was easy, in retrospect; I simply strolled over

to the bed and placed the pillow on the woman’s face. For a moment I thought I

was being watched, thought I saw movement outside the window, and decided it

was my paranoid imagination. The only one watching me, the only witness to my

crime, was my lover. I pressed down on the pillow, a hand on each side.

The old woman did not put up a fight. Her body shook a couple of times and

after a minute or two she became still and the room started to smell like urine

and shit. Gabriella’s aunt (hell, I didn’t even know her proper name, I then

realized) had soiled herself the way people do when they die, when the

sphincter and bladder relax and body waste is evacuated. Gabriella was not

ready for that, she didn’t know about this fact of death. I only knew because I

had read about it, and had, as a child, seen it happen to a dog that had been

hit by a truck—in the dog’s final moments, in the street on a hot summer day,

it let out a single bark and died and shit and peed itself. And my mother: when I found her dead in bed from a

silent heart attack. I was five years old and I shook her and said, “Mommy?”

and she did not reply. Remembering that always froze me. “Mommy, wake up…” “David?” I returned to the moment. “It’s done,” I said, removing the pillow. “Are you sure?” I bent down toward her aunt, trying to detect

breathing. “I’m pretty sure.” Gabriella looked at the woman’s body for a long

minute of hell. “She sure looks dead.” |