EXTRACT FOR

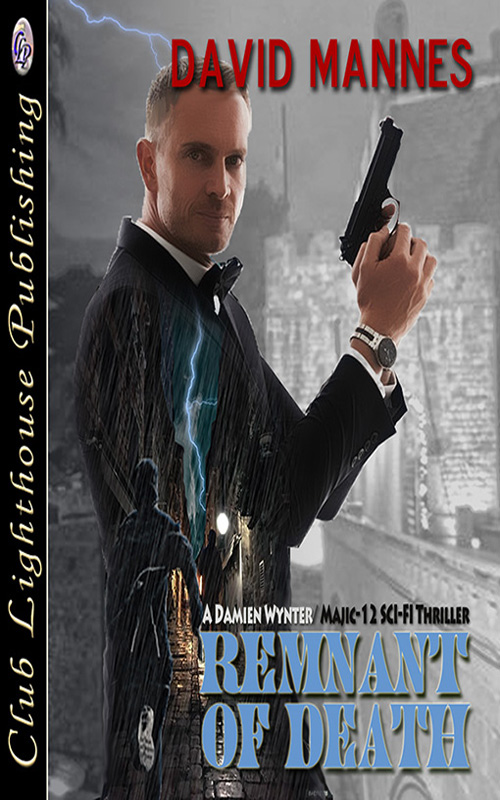

Remnant of Death

(David Mannes)

PROLOGUE

Above the Planet Earth-1908

HALO DOMOR'S SHIP streaked through the single sun planetary system on the edge of the Milky Way. His sensors showed that the Raptonian cruiser was still on his tail. He had taken all the elusive maneuvers he could think of. Unfortunately, Halo was a scientist, not a military strategist. He had undertaken this diplomatic mission to convince the Alcorians to come to his planet's aid against the Raptonian Empire who deemed it their destiny to control either directly, or through economic dominance, all of known space. Domor had hoped to throw the Raptonian's off by charting this path through a relatively unexplored part of the galaxy. As scientist it was not suspicious to explore unknown systems or observe less advanced species. Obviously, it hadn't worked.

"They're still on us." noted Navigator Tofal. A slight, studious man, Tofal was rarely ruffled by any emergency. His grandfather sat on the Council of Elders and had great influence in terms of diplomatic assignments. He felt it would raise the family status if Tofal went with Domor on this mission. Tofal gave a worried look at MarWhen, the husky young pilot. MarWhen merely glanced at Tofal.

Bet you wish you'd stayed at home now you brown-nose spineless wonder, thought MarWhen.

"I can try to take evasive action Sir," he said to Domor.

Though his ship was smaller and more manoeuvrable than the larger starship, they had tracking devices of higher sophistication. A screen flashed on his left. They were targeting them!

"Do so now Mar."

"Try for that third planet Mar," suggested Tofal, "Sensors indicate a tolerable atmosphere. Maybe we can lose them on the surface."

Mar's four digit right hand grabbed the steering rod. The fingers of his left hand flashed across the keyboard. He cut his engines and changed course for the third planet from the sun. The one thing he was almost sure of, was, that the Raptorians would not want to be observed by the planet's inhabitants.

The ship shimmied as it skimmed the surface of the outer atmosphere. A blast rocked the ship, throwing Halo from the command seat. He fell to the floor of the craft, bumping his grey, bald, head-on part of the sensor array panelling. His ship wavered. He quickly clambered up and plopped himself back into the chair.

"Sensors show that our shields are holding," said Tofal. But for how long? This was an exploration craft. It didn't carry arms. In fact, they had deemed it safer since no civilized society would fire on an unarmed craft-or so they had thought. Another blast rocked his ship. Domor held on.

"Sensors indicate that our port thruster engine has been hit," reported MarWhen.

They were playing with them. Halo turned his communicator on and spoke, "This is a Pleiadean Scientific vessel Rosh Mar, Scientist Halo Domor commanding. We are on a peaceful exploratory mission. Why are you firing on us? We have done nothing. We are unarmed. Desist or I will lodge a formal complaint through the Interplanetary Federation when I return."

Halo waited. There was no reply.

Another blast bombarded the ship. The ship rolled and vibrated from the shock. Tofal was thrown across the control centre. He slammed into the life system panel and crumbled on the floor. MarWhen, though strapped into his chair, slammed his head on the steering control panel. Blood seeped from a wound over his right eye. Dazed, he clung onto the steering rod. Halo was again thrown from the command chair. Alarms screamed! Smoke sifted through the vent system. Life support was going offline. He fought the controls as his ship entered the planet's atmosphere.

"Sir, the engines are overloading!" yelled MarWhen.

"We must land!" commanded Domor.

On the planet below a curious thing happened. Huge cylindrical metal tubes thirty feet in diameter rose from hidden silos in the underbrush. They began to hum, harnessing energies deep below the surface of the planet. These defense mechanisms had been built and placed over ten thousand years previously. But they were still operational. A hidden computer complex deep below the surface had been activated automatically from sensors hidden on the planet's surface that registered the energy signatures of the craft that had entered the atmosphere.

The craft hurtled into the atmosphere over one of the planet's seas. The internal temperature was rising in the craft. Thick grey smoke poured through the vents. Mar-When began cutting the engines, trying to slow the craft down, but the controls were not responding properly. Systems were offline. Steering was sluggish. It took every ounce of strength he had. View screens showed that the planet was definitely inhabited by a low technological civilization. Grids of cities and roads were vaguely visible. The planet was lush with vegetation. 3-D screens indicated some treacherous mountain ranges.

"Our shields are down!" cried MarWhen.

"I'll try to get them online again," said Domor. He crossed the cabin to man the engineering station, that had also been the unconscious Tofal's duty.

MarWehn made a course correction. He didn't want to land in an inhabited area. This was a primitive backward planet. They could be at more risk from the local residents than from the Raptorians.

"MarWhen, we must make for the escape pod. We have reactor failure in the engines. The temperature controls are offline. We must abandon ship!" ordered Domor. He staggered across the floor towards Tofal's prone body.

A fraction of a second later the Raptorians fired their final blast. The ship instantly vaporized in an exploding array of bright light. And in response, an energy wave shot out and encompassed the Raptorian craft and vaporized it, setting off another energy wave that hit the planet.

CHAPTER ONE

June 30,1908

8:17 a.m.

Tunguska, Siberia

Russia

VASILY RYCHENKOV, HIS wife, Akulina, and their son Pedrov lived on a small farm in the pastureland on the Tungus. As their Evenki ancestors before them, their home was a simple wood and mud cabin. Vasily trapped small animals. They also had a herd of reindeer, which were grazing in the mountains. A few chickens scratched around a small fenced in pen. They lived a simple life, away from the political turmoil of Moscow. They didn't have to worry about the Czar's soldiers. Though most of the surrounding land was swamp and boreal forest, not good for farming, here in the rich valley they lived quite well. Besides the crops they grew like carrots, cabbages, peas and rye, game was abundant and there were edible plants and roots. The trading post was three days away and when they had gathered enough furs, they would go and get the supplies they needed.

It was a cool morning. Vasily could hear the birds chirping. But there was something else, a roaring sound like the rushing of a strong wind. Vasily got up and ambled to the cabin door and peeked out. There was something bright and silvery with a blazing tail streaking across the morning sky. It glowed with a bluish-white light. And it seemed to be coming in his direction. He turned and went to wake his wife and son. But it was too late.

It had started out as any typical day in the small trading post and village of Vanavara located on the Stony Tunguska River in the central Siberian Plateau of Russia. A bright summer's morning one heard birds chirping. Lush meadows, swampy areas and pine forests peppered the surrounding land. The villagers were going about their early morning affairs feeding livestock, tending to the few crops they could grow such as rye, peas, carrots, and the like. Men were ready to go out into the forest to trap, hunt, fish and cut firewood. It was a typical day like any other, or so the people thought. But they were wrong. The morning calm was destroyed at that precise moment.

Stephanik Semenov was taking a break from working on his cabin. Stephanik, a thirty-five-year-old trapper, was sitting on his front porch having a cup of tea. His dark almond-shaped eyes turned skyward as he heard a roaring sound. He looked up to the northwest and saw a strange silver cylindrical object turn and arch in the sky. And then he went blind. A huge fireball lit up the morning sky stronger than ten suns. Scant seconds later a hot wind of hurricane force blew through the village His shirt seemed to disintegrate off him as he was lifted and flung about like a piece of kindling. The ground shook like a thousand giants marching through. His hut exploded hurling spears of wood and debris in a million different directions.

Popkov Kosolapov was at the trading post trying to find some nails. Not finding any the length he required, he went out into the yard and found some boards with nails in them. He took a pair of tongs from his back pocket and bent over to retrieve them. Suddenly a wave of heat seemed to burn his ears. He dropped the tongs and put his hands over them. And then there was a clap like one hundred thunderbolts and Kosolapov felt himself lifted up and hurled over the yard. He crashed through the fence and all went black.

Three hundred and seventy miles southwest, in the railway town of Kansk, hurricane winds rattled homes. Two minutes later strong tremors upset rafts on the river, dumping its fishermen in the water. Animals ran in panic.

People travelling on the Trans-Siberian Express were shaken and thrown from their seats. The Engineer saw the rails shake and jammed on the brakes to halt the train. He looked out to the north and saw a giant mushroom pillar of cloud take out the sky.

And then silence reigned, though tremors from the explosion would be felt throughout Europe.

CHAPTER TWO

June 1927

Tunguska, Siberia

Russia

LEONID KULIK, A thirty-eight-year-old scientist from the Mineralogy Museum of the Academy of Science in St. Petersburg, gaped at the curious geological horror before him. His piercing black eyes took in the scene through his round, thick, black-framed spectacles. He turned to the rest of the expedition. They too stood in awe. The expedition party consisted of Kulik's assistant Gulkikh, Alex Vozenesensky and Yevgeny Krinov, renowned astronomers from the Irkutsk observatory, Ilyich Vernalesky a middle-aged scientist from the Academy of Sciences, Obruchev, a geologist they had met in Kansk, and a young professor Mikael Karensky a geologist and paleontologist.

It had been an arduous journey into the vastness of Siberia. Kulik's expedition had travelled the Trans-Siberian railway to Kansk, then after tracking down and talking to witnesses, they continued further east to Taishet, a piss bowl of a station. A horse-drawn sled took them north to the village of Keshma where they resupplied. The land became more rugged, mottled with creeks, gullies, and steep hills. They arrived at the beginning of April, ankle-deep in mud, at Vanavara, a village of a few primitive huts and a couple of trading posts. It was there they learned that their destination lay three or four days further north. A local trapper, Ilya Semenov was hired as a guide.

It was still very cold on the taiga. They hiked in, using horse-drawn sleighs to carry their supplies, until they could go no farther. By then, the rivers were swollen and rapid. Making rafts, they travelled down the Chambe River. Days turned into weeks.

And now it was June, and the devastation, over almost two decades in the past, lay before them. It was still astonishing. Amid signs of sparse regrowth, trees lay like piled corpses in the war. Their limbs were stripped, and their trunks burnt black.

Kulik turned to his fellow scientists. "Now our work begins."

They steered ashore. After tying the rafts, they spread out and examined the trees, with their broken branches laying on the ground. They hauled out photographic equipment and took pictures of the devastated area.

That night they camped in a valley near the mouth of the Churgima River. It was eerily quiet. Kulik, and the other scientists sat around a crackling fire. The fire snapped and popped. Brief sparks flew like fireworks. Kulik held a tin cup of tea in his hands.

"Tomorrow we should check out the swamp area," said Professor Vernalesky.

"I'd like to get some soil samples," said Obruchev, a geologist who had been doing research in the area, before joining the group.

An untypical silence descended as night came. The temperature dropped and the expedition team huddled in their tents, wrapped in sleeping bags and blankets. The fire burnt down, and the embers died out like small old suns.

The next morning the group had a breakfast of tea, dark bread, sausage, and cheese. They then packed up what supplies they needed and continued on to their destination. It was hard going. Broken trees and undergrowth made it difficult for hiking. At times they had to hack their way through the underbrush.

At the top of Khladni Ridge they could see the lower ridges stripped bare of growth. Dark scorched earth covered with uprooted trees, all having fallen at the same angle, like piles of spears, their tops facing south or southeast. Scanning several miles, there was nothing but devastation. As they stood on the ridge, Ilya looked at Kulik. "I go no further. This is the devil's land. The God Odgy has cursed this area by smashing trees and killing animals. If I go there, I too will be cursed."

"We need to see what caused this," said Kulik.

"I go back to camp. I wait for you there." Ilya turned and marched away.

"Stupid peasants," spat Vernalesky.

"He is scared. He is uneducated. He doesn't understand meteors, comets," said Krinov.

Vernalesky glared at the young assistant professor. "He is a fool. Come, we shall make our own way." With that, the scientist began carefully making his way down the ridge.

The others followed. Several times Obruchev stopped and took soil samples.

Back at camp that night, they examined their findings. Over a cup of hot tea, warmed with a shot of Vodka, Obruchev made some observations. "I have found silica. The ground was so hot it turned some of the sand and soil to a glass like state."

"So perhaps it was part of a comet that fell," said Krinov.

"Comets are ice. It wouldn't do that. Besides, such matter would burn up in the atmosphere. No, it had to be a meteorite," said Voznesensky.

"But according to the peasants' statements it was silver in colour," said Kalensky. "The sun reflected off it."

"According to some of the witness, it changed direction," said Gulkikh. "I've never heard of a meteor doing that."

"When you look at something coming from the sky, with the sun in your eyes, it can be deceiving," said Krinov.

"There is a swamp to the north. It is called the Southern Swamp. Perhaps what you seek will be there," said Ilya. Of course, that land was probably cursed as well, but not as much as the surroundings they scientists had been exploring. He had watched with some interest as the men tested the samples. It reminded him of alchemists and their wizardry, though some could be used for good.

"You will take us there?" asked Kulik.

"Yes. As long as we don't have to go through the sea of dead forest," replied the guide.

The next morning, they loaded up their packs and set out again. Kalensky and Krinov studied the fallen trees.

"They are scorched like a hot flame," said Kalinsky.

"I agree," nodded Krinov. "These are not the burns of a forest fire though."

Signs of heat flash increased. Everything, ground, trees, shrubs were charred. Ilya began to get nervous. He wished the men would give up and leave. No good would come of this, of that he was certain. Yet, they paid him, and that would ensure food and supplies for him and his family. Trapping had not been good of late. The animals were scarce. Perhaps they were smarter than people and knew to flee a cursed land.

"Could this have been caused by a heat pocket?" asked Kulik to the others.

"I've never seen anything like this," said Vernalesky.

As they continued, there were pockets of depressions in the ground. Finally, they reached the marshy basin known as the Southern Swamp and began trekking around the frozen swamp. All the trees lay out like an open fan.

"This has to be the origin of the blast zone," said Voznesensky.

"I concur. There has to be a crater here. Anything that made this large a blast had to come down," said Krinov.

"We'll need to find samples if we can," said Voznesensky.

"Let's spread out and see what we can find," suggested Kulik. With Gulkikh marching next to him he went off to the right.

Vernalesky and Krinov went the opposite way.

Kalensky checked the ice and cautiously made his way out several yards from shore. He bent over and taking a small pick from his tool pouch, carefully chipped away for some samples.

That night the lanterns burned brightly in the tents as the scientists began testing some of their samples. Kalensky came into Obruchev's tent. "I need you to look at this. It looks like a fragment of the meteorite, though it is quite shiny."

Obruchev pushed his spectacles up on his thin nose and peered into Kalensky's hand. There was a small oval disk of shiny metal. The geologist picked it up and held it close to his eye, then reached down for a magnifying glass off the folding table. He held the fragment up to the lantern and studied it. "I've never seen anything like this. Get Vernalesky, Kulik and Voznesensky in here."

Kulik looked at the small shiny disk-shaped sample. He turned to Gulkikh. "Get the microscope. Let's see what we have under closer inspection.

Gulkikh went to one of the supply crates and returned with a wooden box. Placing it on the folding table she opened it and took out a well-padded microscope.

"Bring the lanterns closer," instructed Kulik.

Kulik put the piece of shiny metal on a glass slide and placed it under the lens. He sat down and looked through the eyepiece and adjusted the sights. He gasped, then leaned back.

Krinov's pocket watch ticked loudly. Everyone waited breathlessly for a few moments. "Well?" asked Krinov.

Kulik stood up and turned, "Go have a look. Tell me what it is. This doesn't look like a meteor fragment. It is smooth and polished."

"The heat could've done that as the object came through the atmosphere," Krinov reasoned.

"If it is rock matter, there are still basic properties that should be easily identifiable," said Obruchev.

"True," agreed Kalensky.

Each of the scientists in turn looked through the eyepiece.

"Well?" asked Kulik.

"I have never seen anything like that. It would be good if we could get a sample to test and establish its makeup," said Voznesnsky.

"I have that small kit we brought. We should do some tests tomorrow," suggested Krinov.

"I wouldn't want to destroy our only sample. We'll see if we can find more fragments like this first," said Kulik.

The next morning, they headed back to the swamp. Again, splitting up into small teams, they set about collecting samples and photographing evidence. Their supplies were limited, but Kulik was sure he'd be leading more expeditions in order to study and try to understand what happened here. That night after dinner, the group discussed their findings.

Ilya watched the scientists. His eyes darted around the forest. The place had evil in it. He kicked at the earth beneath his feet and felt his boot hit something hard. He bent down and scratched at the boggy soil. His fingers grasped a rock of some sort. He picked it up and brushed it off. It was a light brown piece of amber but as Ilya stared at it, he saw something silvery and square inside. He held his hand out towards the sunlight. Whatever was inside, it glittered like the silver droplets he and the scientists had found. Ilya smiled. Perhaps this would be a good talisman that would protect him from the evil. He slipped it into his coat pocket.

"The preliminary tests are quite strange on that silver piece we found yesterday. Kalensky found a couple of more samples today," said Obruchev.

"How so?" asked Kulik.

"I did some preliminary tests on the silver disks. I can't identify the metal. And another curiosity, Kalensky and I found particles of Magnetite and Silicate embedded in some of the surrounding trees. But there was another element we couldn't identify."

"Perhaps," said Voznesensky some more extensive testing will identify it." He took a puff on his cigarette and exhaled a cloud of smoke. "After all, you don't have a full laboratory to work with out here."

"He's right," said Krinov. "There is no use making theories or hypothesis until a full analysis is done."

"The other curiosity is that the trees in the immediate area are unharmed, but all the trees surrounding what should be the strike site are flattened," said Karensky. Flickering campfire light flashed shadows across his craggy young face.

"Still, it tells us that the explosion caused extreme heat, more so than I've seen at any other meteor sites," said Obruchev. He took a puff on his pipe.

"The earth has been hit by massive meteors in the past. The Americans had one hit in their southwest centuries ago. The crater is supposed to be massive," said Vernalesky.

"Yes, but that's the other thing that's missing," pointed out Kulik. "There's no massive crater. According to witnesses the explosion happened before impact. It is most unusual."

"And that's why we are here," said Vernalesky, as he sipped a cup of tea. "To investigate this phenomenon and determine what happened. I don't see us making any judgments until we've gathered all the evidence, and I'm convinced we will need more expeditions to discover the truth."