EXTRACT FOR

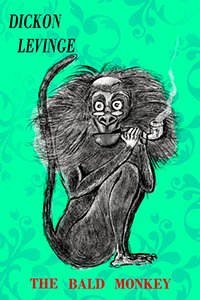

The Bald Monkey

(Dickon Levinge)

Chapter 1: HenryHenry did not consider himself to be

overly precise or controlling about many things in his otherwise chaotic life,

but this was his haven. His isolation chamber, where time became meaningless

and the memories he visited became the present. His cocoon. He immersed himself

in the warmth of the red bulb and inhaled through his nose. Relishing the sharp, vinegarish scent that wafted from

the stop bath tray – which he had lined up exactly between those containing the

developer and the fixer. Taking care that each solution was warmed to the

optimum temperature. Like everybody else in his

profession Henry had, for his day-to-day work, switched over to digital formats

years ago. Lazily snapping dozens, sometimes hundreds, of images on a job.

Knowing that at least a few of them would be good enough to appease his aesthetically

challenged clients. Scattergun photography for the birthday bashes he couldn’t

stand, the corporate events that made him seethe and the lavish weddings he so

detested. Oh, God, the weddings. How he dreaded those most of all. Ugly people

in uglier outfits grinning inanely with unfounded, alcohol-induced optimism.

But at least they paid well and enabled him to continue with his more artistic

endeavours –

along with the absurd mission on which he had, in

recent years, become increasingly fixated. It was this vanity on which today's

darkroom session touched. The negative he chose came from one his older, more

precious files. Black and white. He slipped the celluloid strip into the

enlarger, snapped the gate onto the frame he knew so well and brought into

focus the inverse image of a smiling couple sitting outside a floating

restaurant. A converted passenger ferry, from the 1930s, moored alongside the

Embankment. The London Eye framing them with a diffused halo against a

darkening sky with silver-edged clouds. A bottle of champagne in an ice bucket,

along with three glasses, sat on the table before them. Henry placed the photographic paper

onto the base plate, flicked aside the red safety filter to give it a three

second blast of white light, then moved over to the baths. He slipped the

exposed sheet into the developer and, for what must have been at least the

hundredth time, savoured the memory’s gradual return. Instinctively, it

was Arabella he watched appear. The wisp of hair at her temple that she could

never quite tame. The tiny, fine line at the corner of her mouth. The one he

used to call her smile crease. As the richness of the image deepened, he took a

set of rubber-tipped tongs, carefully removed the print from the developer tray

and transferred it into the stop bath. His younger self stared back at him.

Straggled hair still full and dark. A joyful, vibrant smile. The only sign of

age were his glasses, newly acquired that week. Then he clenched his jaw when, as

always, his attention was stolen by the reflection of the photographer in the

left lens of his new specs. Marion. Arabella’s sister. It was she who had introduced Henry to Arabella some six

months before the photograph was taken. Which was the only reason that, at

times, he almost forgave her for the basic error of capturing her own

reflection in such an important, momentous image. At times. And only ever

almost. Henry took a second set of tongs,

removed the photograph from the stop bath and eased it into the fixer. As it

rested there he focused on the main subject of the image, the detail that gave

it such immense value. Henry’s and Arabella’s hands clasped together and held

above the champagne bottle. Outstretched towards the camera and showing off the

diamond ring that Henry had presented to her just hours before. The first

portrait of them as an engaged couple. The only record of that precious

milestone in the great love story that was their marriage – until it was so abruptly ended. A loud, demanding jingle wrenched Henry back from his

past. Cursing himself for forgetting to switch it off, he removed his mobile

phone from his pocket and scowled at the lurid screen. ‘I’m making arrangements myself,’ a text message read, ‘You should have done it years ago. Shame on you’. Henry seethed. Speak of the Devil’s daughter. No word from Marion for nearly six

years and, now, the third message in as many days. He snatched the photograph out of

the fixer bath, rested it on a table and, bending down, examined it under a

loupe. He focused on the reflection of Marion behind the bulbous, intrusive

lens of his old Nikon F2, which she’d clearly had no idea how to use. How could

she have missed her own reflection? He removed the negative and, again

with the loupe, inspected it with a frustrated squint. Over the years Henry had tried, many times, to remove

Marion’s trespass the old-fashioned way, by blocking and

dodging in the darkroom, but never with an adequate result. He always ended up

deadening his own expression. His all important, sideways glance towards his

beautiful new fiancée. Finally, he supposed, he’d have to resort to the cold and soulless digital method. Henry ripped the photograph in two

and tossed it in the bin. “Drew!” he bellowed as he threw open

the door and marched back into the harsh, glaring reality of the present. Drew, his young, earnest assistant, sat in front of a cinematically huge computer screen perched on the only tidy desk in the

room. Henry handed over the negative strip and said, “Frame sixteen, second in from the

left. Scan, clean and set it up for me to work on later, will you?” Drew replied with a serious nod, which seemed at odds with his fixed smile, and

carefully took the strip in his hand – taking care only to touch the sides. “I’m out for the evening,” Henry added. “Lock up when you’re done.” He picked up a thick, battered file from the maelstrom of paperwork and

glossy images that was his own desk, tucked it under his arm and left. Chapter 2: The Bald MonkeyHenry slapped the file down onto the

bar, knocking over a saltcellar. “Shit.” He took a pinch

with his right forefinger and thumb, threw it over his left shoulder, repeated

the action twice and finished the ritual with three sharp knocks on the

polished oak surface. As he mounted the barstool, he looked up to see Michael,

the septuagenarian landlord whose healthy complexion and thick waves of white

hair could have easily fooled anybody into thinking he was a youthful sixty,

grinning back at him. “Still at that malarkey, are you, Henry?” Michael quipped

in a

musical, Connemara lilt, “You’ll be avoiding stepping on the lines between the tiles

when you’re coming in, next.” Henry glanced down at the polished, porcelain squares that checker-boarded the entire pub, then

looked back to Michael and humoured him with a forced smile. “Pint?” Michael asked. “Please,”

Henry replied, then turned his attention to the file.

He flicked it open and leafed through an array of faded

documents, old maps and photographs of dank, brick lined tunnels. As Henry

studied one of the maps a massive hulk of a man

wearing workman’s trousers and an old donkey jacket, plonked himself

onto the neighbouring seat. He glanced at Henry’s file and rolled his eyes. “Oh, for fuck’s sake,” he grumbled. Henry flicked the newcomer a

sideways glance just as Michael appeared with his pint of ale. “Cheers, Michael. One for Des here

too, if that’s okay.” “I’m sure it is,” Michael curtly

replied, regarding Des with a less friendly expression than that with which he

had greeted Henry. “Snakebite,

Desmond?” “Yeah. And a shot of tequila.” Des squinted down at the map. “I’ve gotta feeling I’m gonna need it.” Michael looked to Henry for

approval, which duly came in the form of a smile and a shrug. “Go on, then,” Des reluctantly

asked, “Let’s see what you’ve got.” Henry grinned and pushed the map

towards his friend, “I think we missed a section.” “Did we.” “We did. Here.”

Henry circled a small square on the map

with a China marker. Out towards the edge and near a thick, blue curve that

signified the River Thames. “That’s Embankment. I took you down there yonks ago. Fucking

years back.” “Language at the bar, Desmond. We’re a family establishment in here.” Michael chided as he placed Desmond’s drinks onto the bar. “Sorry, Michael,” Des replied in the tone of

a grumpy teenager. Then he cheerily

asked, “Groucho been in yet?” “Please don’t call her that,” Henry groaned.

“Still sixteen minutes to go,” Michael replied, gesturing to the wall clock which read sixteen minutes

to six. “Fuck, we’re early today.” “I’m serious, Desmond. If you’re going to use that sort of

language then you can move to a table and keep the volume down. In fact, you

should do that anyway. It’s going to get busy later and I’ll be needing the bar space.” “Yeah, alright,” Des replied,

the teenage angst back in his voice, even though the giant of a man was well

into his fifties. Although not as well into them as his grey stubble and

life-beaten face might have suggested. Henry gathered up his file and his

drink. The duo moved across the spacious room dotted with high, round tables

and barstools to an opulent, red leather corner booth. Sixteen minutes later Sonia – a

tall, thin, pinstriped woman with a mop of jet-black hair and thick, black

eyebrows above thicker, blacker, plastic framed glasses perched on the bridge

of her prominent nose – bounced through the front door. She looked around the

pub, saw Henry and Des sitting in the booth, frowned quizzically and then

approached Michael. After exchanging pleasantries with him while he poured her

a large gin and tonic, she took her drink and loped across the room to join the

two men. “What are we doing here? Why aren’t we at the bar?” she matter-of-factly enquired with a clipped cadence

possessed by the ghost of an Eastern European accent. “Dizzy’s fault,” Henry replied with a wicked grin, “He kept swearing so Michael exiled

us to the tourist section.” “Arsehole,” Sonia scolded, glaring at Des as she sat, “I hate not sitting at the bar. That’s where all the action is.” “Wouldn’t have mattered,” Des sulked, “Michael said we’d have had to move, anyway. Says it’s gonna get busy tonight.” “Yes, Des. Busy. As in action!” After taking a long sip from her drink she looked down at the table,

spied Henry’s document and excitedly

added, “Ooh! You’re off on another of your expeditions!” “No, we are not,” Des snapped. “Yes, we are,” Henry corrected. “When are you going?” Sonia grinned. “We ain’t,”

Des insisted. “When are you going?” Sonia

repeated. “Tomorrow night,” Henry smiled. “Oh, for fuck’s sake.” Des knocked back his tequila with a frustrated gulp. “Pick you up about eight outside here, Dizzy?” Henry cheerily suggested, to which Sonia let out a

loud, cackling laugh. “Yeah, all right,” Des sighed. “Better make it nine, though. I’ve got a job on.” Henry and Sonia ceased their

laughter, shared a quick look and quietly sipped their drinks, the atmosphere

suddenly taking on a more solemn air. “Nine will be fine, Des.” “Last time, Henry. Promise me.” “Last time, Dizzy. I promise. There’s nowhere left to look. Anyway. Come

the end of the month it won’t really matter. Marion’s calling it.” Then it was Sonia and Des’s turn to share a look of concern. “It might be for the best, Henry,” Sonia tentatively suggested. Henry’s jaw flexed but he passed no comment. He forced a

smile and cheerily asked, “Another round? My shout.” “Well, now, that sounds just marvellous!” Sonia beamed. “Yeah. Don’t think I can, though.” said Des, taking the other two by surprise. Then they saw that he had

locked his gaze on a small, wiry man with sharp, darting eyes behind spotless,

wire frame glasses. Evan, who stood at the end of the bar, summoned Des with an aggressive jerk of his bony head. Des finished his snakebite, swilling

the last sip around his mouth as if it was mouthwash, nodded his goodbyes and

stood. The other two watched as he joined Evan – Des towering over him and yet

appearing smaller, almost diminutive, as they exchanged a few words while Evan

discreetly handed him a thick, grubby envelope. As Des left,

Evan threw Henry and Sonia a hard glare, before retreating to a high table and reading a tatty, heavily thumbed copy of The Sun. Sonia and Henry turned back to face

each other, both with grim faces. Until Sonia smiled, and in a light, airy voice declared, “Tonight, dear Henry, I am of a mind to get rat-arse

pissed!” Chapter 3: Thanksgivings and MisgivingsShortly after closing time Henry and

Sonia rolled their way down the hill that is the straight, wide and tidy

Gloucester Avenue. A boulevard running the length of Primrose Hill that’s more

akin to the thoroughfare of a rural village than one in the centre of a great

metropolis. Henry staggered only slightly, and that was mainly due to him

having to support Sonia who, several gins and a bottle of wine later, had been

more than true to her declaration. Sonia rambled, as she usually did in her

inebriated state, yet still managed to remain coherent. On this occasion, she rebuked Henry for not pulling

his weight in helping her prepare an exhibition of his work that her gallery

was set to host at the end of the month, in three Thursday’s time. The last

Thursday of November. “That’s Thanksgiving, you know.” Henry slurred. Then he frowned as he wondered if he might, in fact, have been a little more drunk

than he’d given himself credit for. “I couldn’t

give a toss, Henry!” Sonia snapped. “Why would I give a toss about an American holiday? You know how I feel

about Americans these days.” “I thought he was Canadian?” “Oh, it’s all the same, fucking thing! They’re all bastards. And they all

celebrate Thanksgiving.” “Actually, Canadian Thanksgiving’s on a different day. I think it’s a month earlier.” “Jesus, Henry, what part of me not giving a toss don’t you understand? I’m trying to make a serious point, here!” By the time Sonia was making her serious point they had reached the

bottom of the hill, meandered through a small alley and were just turning onto

Regent’s Canal’s towpath. Left, towards Camden. “The early invitations went out yesterday. The space is

empty, waiting, and you haven’t even chosen half of the photographs, let alone had

them printed and framed!” Henry nodded in serious agreement as

he moved around Sonia, placing himself between her and the water as she slipped

and stumbled a little too near to the edge for his comfort. “I mean, it’s serious, Henry. Oh, I see what you did there.

Thanks. And don’t change the subject!” “I didn’t

change the subject.” “Yes, you did. You were banging on about bloody Thanksgiving. Which is

not the reason you chose that date for the show. And you know it. And, by the way, the rest of us find it a little weird.” “Oh, God, not this again.” “Yes, this again. I mean it, Henry. It’s creepy.” “It’s a coincidence. You always have these events on a

Thursday. This year, that date just happens to fall on a Thursday.” “Ha!”

Sonia snapped, stopping both of them

in their tracks by reeling on him with an accusatory finger-stab and a gotcha

expression. Then she looked away and frowned, wondering if she had actually caught him out on anything, before realising she

probably hadn’t.

So she smiled, linked her arm through his and allowed

them to continue on. Sauntering and swaying under the

rounded, brickwork arch of a small bridge and past old, converted warehouses – once factories and storehouses, now expensive flats

and extortionate coffee shops. “All I’m saying is that you need to get on

with it,”

she mumbled, then fell silent as they walked over a

humpbacked, pedestrian bridge that crossed the canal. They passed the lock gates, weaving between and stepping over late-night

drinkers, hollow-eyed homeless people and a determined busker, at least as

drunk as Sonia, who strummed an old guitar with only four strings while

groaning out the garbled lyrics for Fairytale of New York. “A bit early in the year for that number, isn’t it?” Henry said as he slipped a five pound note into the musician’s open guitar case. The player looked up with wide, vacant eyes and gave

a grateful, toothless smile. Sonia

randomly declared another loud and victorious, “Ha!” before, again, resting her head onto Henry’s shoulder and, her eyes half

closed, allowed him to guide her onto the next main road. Two hundred yards further on they

came to a halt outside a red-bricked, Victorian warehouse, the door of which

was surrounded by colourful, ceramic tiles. Most of the tiles were cracked and

the building’s brickwork appeared in desperate need of repointing. It seemed to be the only structure in the area

that had not, in recent years, been renovated. Above one of the windows, with a

white, empty room beyond, hung a sign which read The Sonia K Gallery. “Got your keys?” Sonia rummaged around her leather

backpack, found an oversized bunch of keys, fumbled with them while trying to

get one into the lock and then stared down, slightly swaying, as they fell through her overly relaxed fingers. Henry

bent down to pick them up. Then he stopped still when he saw they had landed on

the manhole cover just outside the window. He gave slight shudder, eyeing the steel plate with a feeling of dread, before taking a quick

breath, retrieving the keys and unlocking the door. Sonia smiled, gratefully, then

looked up at one of the first floor windows and dramatically said, “Living above the shop. Has it really

come to this.” “I’m afraid it has,” Henry replied with an

equally theatrical flair. It was a well-rehearsed exchange that he and Sonia

had conducted many times and, as always, it continued with Sonia smiling

warmly, wrapping her arms around Henry’s waist, drawing close to him and

whispering, “Are you coming in?” As he always did, Henry placed his

hands on her shoulders, gently eased her away from him and quietly replied, “No,

Sonia. I am not.” Sonia shook her head, disappointed

but unsurprised, and said, “It’s been six years now, Henry.” “Nearly seven, Sonia.” “Ha!”

This time she knew she had him. “Exactly! Nearly seven years, Henry.” Henry said nothing. Sonia then folded her arms, leant

against the doorframe and, after taking a thoughtful moment, quietly added, “You know, this might be the last

show I get to do here.” “What? Why?” Henry said. The usual doorstep conversation now taking a new,

worrying digression. “Oh, the usual. Money. Thanks to the American. Canadian. Whatever. Shit-bag. And, just look around,” Sonia gestured, with a wide arc, at the surrounding buildings. All

pristine, new and soulless. “Bankers to the left of me, developers to the right.

And, here I am.” “Stuck in the middle –” “Stuck in the fucking middle!” Sonia

raucously laughed. Then she leaned in towards him again. This time to give him a warm, affectionate hug. “You need to start being less passive about everything,

Henry. Get more proactive.” Henry smiled as she returned to her

normal agenda of how to fix Henry. “And I don’t just mean about the show.” She gave him a kiss on the cheek and retreated into

the gallery. “Although, don’t get me wrong. I do mean mostly about the show,” she

laughed. And was about to shut the door when she turned back to face Henry with

a hard, sullen expression. Quietly and soberly she said, “I’d kill him, you know. If I could.” “Who?” “The Canadian. If I could, if I knew where the hell he was, I would hunt him down and I would kill him. Strangle him. Were the opportunity to

arise, I’d wring his devious, thieving, beautiful bloody neck.” She held a dead-eyed stare for a moment, then snapped

back to her usual smile as she gave another wink, clacked her tongue and blew

Henry a final kiss. “Night, Henry. And fucking get those prints organised.” Sonia closed the door and Henry

stepped back to watch the various lights turn on and off as she made her way

through the gallery space, up the stairs and into the small, top floor flat.

Satisfied she was relatively near her bed, he made his

way down the road. At the first crossroads, while waiting for the light to

change, he turned back and looked up at the gallery. The stained glass window

above the worn out door. The cracked tiles and the neglected brickwork. Nearly seven years, he thought. Remembering that night when his life, or

at least all that was worth living it for, came to an end. |