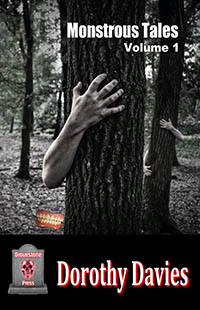

EXTRACT FOR

Monstrous Tales - Volume 1

(Dorothy Davies)

Visiting GranddadSJ Townend Despite the doctor telling him to cut back on the fried food, the toffees, the protein, if Granddad was cooking himself dinner, he was cooking something he damn well liked. Tonight it was greasy and meaty. Bah humbug to the Vegan Youth and the ‘meat is murder’ brigade. He’d been a young boy in the fifties when meat was a privilege, meat had been a luxury, so no doctor was going to tell him what he could and couldn’t eat. He put his teeth in a bourbon glass next to his plate, acrylic smiling at porcelain and sat down next to Grandma to start his supper. Knock, knock, knock. The door. He chose to ignore it. He pierced the ox tongue with his fork, anchoring it to the face of the plate and drew his favourite steak knife back and forth and back and forth until a morsel large enough to enjoy but small enough for toothless mastication hung speared on the end of his fork. He chomped on the soft gobbet, bashing and smacking it against his gums, eyes closed and mouth opened and let out an audible moan of delight as the blood in the meat released and trickled into his palette. The knock at the door was repeated. Damn them, coming now. We’ve just sat down to eat, he thought. With a bony finger, he tapped Grandma on her shoulder. She was a little hard of hearing, silly old mare. Chair legs scraped on the cold stone floor as she rose from her place at the table. “Hi. Sorry, I thought you would’ve already eaten.” It was their daughter Lisa and grandson Billy. Granddad wiped a rivulet of crimson from his jaw as Grandma ushered the pair in. With a spindly arm and no words but a grumble, he gestured at the sofa—all leather and sticky with the heat of the evening—and the boy sat down. Granddad continued with his food. “It smells like liver and onions in here, Grandma. Are you eating offal again—?” Lisa stopped mid-sentence as her father threw her a look which hit like a cold hand, a physical strike from a time long ago when it had been acceptable to spank. “No, dear, I’ve gone for a low-fat quiche,” said Grandma. “Thanks for having Billy.” Lisa was on her way to work. “Perhaps you could teach him how to play chess or show him Granddad’s old fishing rods?” She’d managed to secure a second job at the drive-through, serving coffee to juggernaut drivers and cops. She’d needed the additional income since the kid’s father had up and left. “I’ll be here at eight thirty tomorrow morning to pick him up.” Grandma nodded and smiled at her daughter. Lisa noted how much happier Grandma seemed these days; she had quite the metaphorical spring in her hobbled step. “Just make sure you’re no later than eight thirty tomorrow,” Granddad hissed, not even looking up from his meal. “I’ve treatment at nine.” With a lean stare, he looked at the boy, held his glare a little longer than the boy found comfortable, then returned his attention to his dish. Billy looked at his mother and wondered if she had caught Granddad’s displeased look too. “Everything Billy needs is in his bag. Just remind him to brush his teeth before bed, if you could.” The old man’s eyes flicked to his own teeth in the glass and back again to the boy. Billy’s eyes were drawn to the ticking sound coming from the mantelpiece. In his home, the mantelpiece was crowded with photographs of him and his mother, ornaments, paintings and pieces he had crafted at school. Here, the mantelpiece was bare. Barren apart from a heavy, antique vase, a blanket of dust and an eerie bronze carriage clock that looked older than Grandma and older still than Granddad. “Too-da-loo,” said Grandma, as Lisa, swept up in the struggle of motherhood and work and the ever pressing hand of punctuality, hugged her son and left. Billy pulled a book from his bag. He knew not to disturb his grandfather whilst Grandma pottered in the kitchen. He had brought plenty of books to read—on Sauropoda and the Jurassic era—so he could hide behind the pages, two hundred and four million years away, until he was sent to bed, until his mother picked him up in the morning. This was the second time his mother had left him there overnight since they had moved back from the other side of the country to her home town, after the messy divorce. The first time had been no fun at all, despite Grandma playing draughts with him and showing him how to knit. Billy was a good boy and knew his mother needed the money, so he had quietly got in the car again to stay the night with his grandparents. He really just wanted to run and jump and play as he was an active boy, full of beans, but he knew his grandparents would not want to do any of those things. Granddad was old and Granddad was also unwell—he’d been in and out of hospital for months, Mother said he was in need of a long rest—and Grandma walked with a cane. Mother had told Billy about Granddad needing ‘die-ali-sis’. His body couldn’t keep his blood clean. His body had given up. Mother had explained about the machine which helped to keep him going. He’d asked his mother to explain what she’d meant, but she just muttered something about kidneys. Was it why Granddad ate so much bloody food, organ meat, he pondered? Granddad certainly had the diet of a carnivorous dinosaur, but Billy thought he looked more like a grey tortoise when he chewed bluntly on his meat. *** Billy hated kidneys. Steak and kidney pie, kidney bean chilli: his two least favourite meals. He was glad that Grandma catered for him and Granddad never offered to cook. He’d seen the inside of the old man’s fridge. He kept a separate one out in the garage, additional to Grandma’s one in the kitchen. Granddad made him look in his garage fridge the last time he’d stayed over, after he’d asked Grandma for more dessert: tripe and sweetmeats with nothing sweet about them, black pudding galore—not a vegetable or fruit in sight. “Look here, boy. Stop hassling your Grandma for sweets. You need more protein in your diet to keep you healthy and strong. Sweets will rot your teeth,” Granddad had said to the child. After showing him his fridge, Granddad grabbed the boy, opened his tortoise jaw and showed the boy his red raw gums as close as he could without placing the child’s nose inside his mouth. Billy recalled that his breath had stunk, bitter like decaying flesh and cloying like funeral flowers. The only redeeming feature of Granddad’s diet, as far as Billy was concerned, was the jar of toffees he’d spotted on his first visit. It sat on the top shelf in the lounge, full to the brim last week, silently shouting promises of sugary licks all evening to the boy’s rumbling stomach. Granddad hadn’t offered him one, though, and the boy had been too scared to ask. He couldn’t have reached the jar even if he had dared to try, but alas, he could see it was now empty. Sucked dry, no doubt, by the greedy old man. *** After Granddad had eaten, he popped his teeth back in and sat in his chair by the fire to work on a crossword. Sometimes he stared at the child with an intimidating expression: a smidgen of contempt, a scornful face of disdain. At other times, he stared at Billy with the same look that he held each supper, whilst carving the pieces up small enough for his palate to cope with: a hankering, a thirst, an impatience. Billy didn’t like it when Granddad looked at him and liked it even less when Granddad asked questions, so Billy bided his time whilst his Grandmother darned old stockings. He hid all evening behind his book until he was sent off to bed. The following morning, Lisa came to collect her son. She smiled with all her face and kissed Billy on the cheek. “See you Friday then—if you’re still okay to have him again?” “Sure, would love that,” Grandma replied, smiling with her full face too, like a sunny Saturday. “We’ll have him,” Granddad whispered, smiling with only his pallid lips as Lisa waved goodbye. Then Granddad went out to the garage after checking on his meat supply, folded himself into his car and headed to the hospital. THRICE A WEEK. FOUR HOURS A POP. PUNCTURED. TUBES. ALL HOOKED UP. GOODBYE TOXIC WASTE. SIT. SIT. SIT. BLOOD COME OUT. BLOOD GO IN. CLEAN AGAIN. CLEAN AGAIN. CUP OF TEA. TICK TOCK, HOME TIME. *** That Friday, Billy was dropped off at his grandparent’s again and immediately burrowed into his book as Granddad dined on slivers of brain dripping in a red-brown gravy sauce. The house smelt like the old fox’s body Billy found under the decking in the basement of his old home, awash with maggots, a space where an eye once existed. Billy missed his old house. The boy felt his stomach flip with the sensation of erupting vomit as the old man sliced and chomped on piece after piece of congealed meat. As he watched, he thought about the fox. With fearful eyes poking over the top of his book, Billy couldn’t help but look at the glass with the teeth in it and the congealed mess on the old man’s plate whilst Granddad focused solely on his meal. At nine, Billy was sent to the spare room and he was glad to go. His Grandma kissed him on the forehead and read him a story, then he got into bed and pulled the itchy sheet up to under his chin, to make sure there were no gaps around the edges for things of the night to get in. Turbulent dreams of Cyclops-fox corpses and cutlery teasing and tearing at animal flesh followed and, as he turned over mid-nightmare, he abruptly awoke, releasing a loud scream of pain. He flicked on the dusty lamp beside the bed and shrieked again at the red sight before and around him. Blood. A wound in his side, leaking vermillion liquid onto the crumpled bed linen, gleaming in the only light of the night, yelled for his attention. He pressed his hands against his flank, probing for the source of his injury to find a slice of glass, triangular, sharp like a dinosaur tooth, pressing in to his flesh and as he wriggled to try and see the damage it’d done, he sliced himself again. The boy jumped up and out of his bed and switched on the ceiling light. A buttery glow revealed a sea of shards, mostly in his bed, from where a smashed glass had shared itself around. And there, by the side of his pillow, like a fish out of water and dead, his grandfather’s teeth sat. The boy stemmed the flow of blood from ribboning further down his side with tissues, and then, in the hallway he saw his Grandfather. “Good Lord, boy. What’s all the noise about—are you trying to wake the neighbours?” “Granddad— ” The boy’s pulse quickened at the sight of the old man stood there, dressed still in his day clothes, minus his teeth. Billy’s heart pealed for his mother. “What are you doing, Boy? Let go of the tissue. You need to let it bleed.” “B... bleed?” he stammered. “I think I need to make it stop, that’s what Mother would say.” Granddad let out a hiss, shook his head at the boy and then shook his head again at Grandma as she approached—slowly, hobbling—before trundling back down the hallway. Grandma, cane in hand, shuffled into the boy’s room, her eyes widening at the sight of the smashed glass. “Grandma... Grandma... I’m hurt,” the boy said and carefully tiptoed towards her, pointing at his side. His Grandma wrapped an arm around the boy, comforting him as he cried. “There’s nothing there boy, nothing. You’re fine. Your eyes are playing tricks on you, like my ears fool me in the silence of the night. Now stop all this kerfuffle. Help me clear up this mess.” On hands and knees, the old woman and the boy slowly collected the shards, wrapped them up in newspaper and disposed of them in the bin. She tucked him up in fresh sheets and kissed him on the forehead before leaving him alone with only the light of the bedside lamp for company. Until only moments after the boy’s heart rate had dropped to a level at which the call of sleep could be heard, Granddad returned. “What in heaven’s name are you doing with my teeth, boy?” his grandfather sneered. “Your mother would be furious to hear how you’ve been meddling. If she was to catch wind of any of this, my God, boy, she’d skin you raw. That woman has enough on her plate.” With that, the old man crouched and snatched his teeth from where they’d fallen under the bed. Billy sat shivering and dabbing at imagined blood until his mother came to collect him the next day. In the morning, an exhausted Billy left with his mother. Grandma prepared lunch and Granddad went again to Nephrology. SIT. SIT. SIT. BLOOD COME OUT. BLOOD GO IN. CLEAN AGAIN. CLEAN AGAIN. TICK TOCK, HOME TIME. *** The following week, Billy had not wanted to stay at his grandparents. He’d pleaded with his mother to let him stay with her, but she told him he needed to go, he didn’t have a choice and, in fact, he needed to spend a little longer there this time—she would be dropping him off after lunch. |