EXTRACT FOR

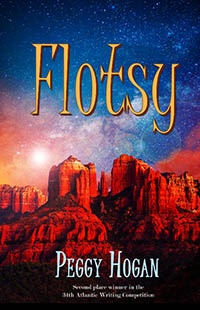

Flotsy

(Peggy Hogan)

Chapter 1I was born Olivia Marie Ducharme in a little fishing village on the east coast of Canada. The Island was beautiful, but I only realised that long after I had left. Living close to the sea, I was forever in the cold Gulf water swimming with the other children, and the fish and the crabs and the lobsters. Afterwards, my penchant was to wander off alone along the beach seeking treasure washed up with the tide and collecting anything and everything that caught my eye—rocks, shells, bits of driftwood—and string them on old fishing line or the occasional piece of rope. Sometimes I would braid these necklaces through my long, dark hair or wear them around my neck and wrists and ankles. I so festooned myself with these marvels that I looked like flotsam moving on dry land. Flotsy, the other kids called me. I loved it; it made me feel like I belonged. One morning, just after my thirteenth birthday, I woke with a burning need to stop the village from extending the old dock deeper into the bay; I had no idea how to do such a thing, I just knew it was a very bad idea. At breakfast I pleaded with my mother and father to help; they smiled and said that I had just had a bad dream. But I could not stop myself from talking about it with everyone I met until the school mistress called my mother and said how it was distracting the other children from their lessons and would she please, please, please make Flotsy stop talking about the bad dock. My mother stormed over to the school and dragged me out of the classroom to the stifled giggles and wide eyes of my classmates. I was ashamed and dreaded the beating when we got home—my mother was angrier than I had ever seen her. The dock was to be lengthened so larger boats could sell their catch to the cannery that was considering our village as the location of its new plant. The village council thought that demonstrating how well the community worked together to attract their business would impress the cannery owners. But I knew, just knew, that very bad things would happen if they disturbed the old dock. It haunted my dreams. I saw the new tarred timbers being lowered into the water and the winch slowly working its way loose in the ancient planking. It had worked hundreds of times before, my father said to me, why would it fail now? He told me this over and over as I stood teary-eyed before him to tell him that I had had the dream again. He would pull me onto his lap, even though I was a newly minted teenager, and smooth my sleep-mussed hair with his callused hand and send me back to bed. I begged my mother to make him stay home the day that the huge logs arrived but by now my entire family, and quite possibly the entire village, was very tired of my constant harangue. I sat at my desk in school that day but heard nothing of what Mlle Blacquičre said. The third time I was reprimanded, I blindly accepted my punishment and began cleaning the dusty, chalk-filled brushes, not even bothering to protect my good school clothes. When the alarm was raised and everyone rushed out the door to see what had happened, I just sat on the steps, tears streaming down my face. I knew exactly what had happened—the metal rivets that had been slowly working their way loose, had ripped from the dock in a sudden surge. The huge log cradled in the thick chain plunged down onto the two men who laboured at the pulley. They barely had time to look up before it shattered the planking beneath them, dragging them and the heavy winch mechanism into the water. It was over in seconds. The foreman had his best divers in the water in moments, but it was already too late. I knew that my father’s skull had been given only a glancing blow, but it had been enough to kill him instantly. Gilles, his partner, was unconscious when he entered the water but was very dead by the time he was extracted from the wreckage. My father’s body lay in the front room, but I could not look at him. Pain was etched deeply into my mother’s face and my two young brothers looked scared and bewildered. No one stopped me when I left the house and walked down to the beach; I could feel their relief pushing me further and further away. It was my fault. It was my crazy dream and my crazy talk that had made this happen. Premonitions were simply never discussed; people who lived off the sea knew that. To do so was just plain bad luck. That was what everyone thought—I had brought the bad luck and it had killed my father as punishment. The new cannery was finally located in the

next village over; they said it would take us too long to repair the damage to

our dock. The fishing that year was bad; there was nowhere to easily put in for

unloading the catch while the dock was being fixed. Of course, all of this was

also my fault. I had cursed the village. The next four years passed like a kind of torture for me. I felt slightly dazed a lot of the time because I made myself stay awake for as long as possible night after night. I would wander aimlessly around the village, which gave me a whole new air of weirdness that I definitely did not need. But, even more so, I did not want any more dreams. “Mais non! T’as l’air d’une folle!” my mother yelled at me one day as I was leaving for another tedious day at school. Not very imaginative of her―she always thought I looked like a fool, and she always spoke French when she was mad at me, as if I didn’t understand her, as if anyone within earshot couldn’t understand her. The problem was that she didn’t understand me. She never saw how the other kids crossed the street when they saw me coming; she never heard the Gallant boys sneering their cruel words at me; she never witnessed the teachers manoeuvring me to the front of the class so that the other kids wouldn’t have to worry about me sitting behind them, making them twist around to look at me every two seconds, though what they thought I would do to them I couldn’t imagine. My one friend, Jacinthe, thought that maybe it was because my eyes were a little spooky. When I studied them in the mirror to see what she meant, they looked like everyone else's eyes to me. She was right, though, almost no one looked straight at me, not even my mother. As was my usual habit when I wished to ponder something, I meandered down to the beach, stooping to pick up whatever caught my eye as I went. The finger-shaped translucent shells in my hand were quite lovely and I studied the beach in earnest for other bits with which to fashion I-knew-not-what. A pointy piece of driftwood looked useful as did the length of net webbing. I sat down and tried to pierce a hole in one end of a shell. Not surprisingly, it split, but right down the middle. The shell halves were about as long and wide as my index finger with small bulges at the tips where whatever mollusc who had lived in it had anchored itself. I picked apart strands from the net webbing and soon had a good length of the strong, thin material. I secured it around the bulges on the ends of the shells until I had a little curtain of dangling half shells. On impulse, I tied it around my head so that the shells obscured my eyes, and when I moved, they clicked and clacked. Through the translucent slices of shell my view of the world came and went in between the pearly light. That was why my mother was mad at me that particular day. She hated the

new fashion I had created for myself; she thought I had gotten over gathering

bits of stuff from the beach and wearing it. I should have waited until I was

out of sight of the house before I had tied it around my head, but I had

forgotten. If my mother took it away from me, I would just make another one. She knew this. “Vite! Je ne veux pas te

voir.” That stung, and I cried, but only a little. I guess I was getting used to people not wanting to see me. The decision came upon me in a rush. I had had all the schooling I could stand, and I was old enough to leave home. Monsieur Arsenault would be making his weekly trip to town the next day; I would ask him for a lift to the bus station. When I declared my intention to my mother, I tried very hard not to see the there-and-gone relief in her eyes. My brothers shrugged and returned to whatever it was they had been doing; for my part, they had never been more than nuisances I cleaned up after. My friend, Jacinthe, gave me a hug and promised to write when I had an address. With some clothes in a ratty old suitcase and a few dollars in my pocket, I boarded the bus. I was going off-Island to a city where nobody knew me or my curse, where nobody shunned me, and where nobody would care about me―that, sadly, would remain the same. Chapter 2After the bus left the Charlottetown station, a great weariness settled on me and I slept while I was transplanted from the only home I had known. I woke much later with a stiff neck and rubbed it as I blearily squinted out the grimy windows. We had arrived somewhere—I had forgotten the name on the ticket; it didn’t matter anyway—and everyone was leaving the bus. In a daze, I followed. There were more buildings and people than I had believed, in my naďveté, were in the entire world. The noise and confusion at the bus terminal made me feel small, in an alien place, lost like the bug I watched circumvent the toe of my shoe and skitter around and around the piece of detritus next to my foot. The bug probably knew exactly what it was doing, which didn’t say a lot about my own survival skills. In my peripheral vision, a bench emptied of its occupants. I shuffled over and sat down, needing to regain my equilibrium. I sat there for a long time, and the details of my surroundings began to filter through. People were in a terrible hurry; they must have very important business to attend to or perhaps they were late for supper. My mother hated it when I was late for supper. Kiosks selling newspapers and pop and other sundries were strewn about the perimeter of the terminal. I should buy a newspaper, I thought. It would list places to stay. I froze. Tonight would be the first time in my life that I would sleep somewhere other than in my own bed at home. Tears stung my eyes and I scrubbed them away, furious that I could weaken so quickly. This wouldn’t do. I was likely just hungry and rummaged through my shoulder bag for the sandwich my mother had shoved in there as her parting gift. I bit into the mayo and baloney and closed my eyes. I would be strong and make a new life for myself. I would be someone that people wanted to be with just because they liked me. I would be a person of value. Composed once again, I opened my eyes and, for the first time, really looked around. My gaze fell upon a homeless man. I had read about homeless people but had never seen one before. He seemed relatively content but who knew how people really felt? Not even me who, for some unknowable reason, received glimpses into their most intimate moments―their most intimate future moments, future moments in which something bad inevitably happened to them. Reinforced by food and rest, I did my best to nonchalantly stroll over to a bulletin board crammed with bits of paper advertising all manner of things for sale and, happily, rooms to let. I spent some of my meagre hoard of cash on a detailed map of the city and wrote down the information for a few rooms that looked to be within walking distance. But, being my first time in a city, I miscalculated the size of city blocks and had to walk much farther than I anticipated, and, tired and footsore, I mounted the steps of the closest address. The woman who answered my knock looked me up and down and shut the door in my face. Stunned, I stood there not understanding for a moment what had happened. I had been judged and found wanting. Just like that. I reminded myself that it was my choice to come to a city and trudged to the next address. It was getting dark. This time, my knock was answered by a young man. He asked me questions for which I had no answer like where had I worked and did I have any references. I think I must have looked pitiful because he took pity on me, and the money for one week’s rent, and let me in. The room was tiny and at the top of three flights of narrow stairs. Exhausted as I was, I didn’t notice much else besides the bed, took my shoes off, and lay down fully clothed. The rest of my life could wait until tomorrow. I woke early as usual and swung my legs over the side of the bed, eager to take a look at my new world. To my right, the morning sun streamed in through a dormer window that had its very own sitting bench. On my left was a chest of drawers, and beside it, a small desk and chair. Opposite the bed was the door with a coat rack of sorts nailed into it for hanging things. I was enchanted. Eager with anticipation, I stood and looked out the window. At first, I couldn’t quite understand what I was seeing. It was as though a sea of grey waves had solidified and was punctuated by mysterious eruptions. Like wiping a smear from the glass, the view resolved into rooftops and chimneys and steeples. Something wasn’t right, though. It took me a moment to put my finger on the source of my unease: there was no water anywhere to be seen. I felt like I was suffocating and frantically tried to open the window. It had a locking clasp. My fingers strained to turn it; I was getting desperate. It gave at last and I pushed the window up, sucking in the air. It helped, but it didn’t smell right—there was no tang of salt and seaweed. I wondered how many more unexpected jolts awaited me. I told a little white lie to get my first job, not the best of beginnings. Who would have thought that you needed to be eighteen to wash dishes? I was seventeen and been washing dishes since I was five years old! But the job paid in food and enough money to get by. With my head down scraping at the pots and pans, I barely spoke, other than a mumbled acknowledgement when more dirty dishes were piled beside me. After a couple of days, I was getting a bit lonely, truth to tell, and on a break later that week, one of the waiters was outside smoking a cigarette. It would have been rude not to say hello. We chatted about the weather and the work at the restaurant and he seemed like a nice fellow. He was older than me, but it was still nice to talk to someone. That is, until our eyes met for a moment. His glance skittered away. You would have thought I had suddenly grown fangs or something. He dropped his half-finished cigarette and hurried back inside. When I walked in a few minutes later, everyone stared at me as though I was a dead rat. I hurried to the sink and applied myself to the dishes, working furiously. Before the end of the day, the manager took me aside and said that my work was unsatisfactory, and was letting me go. No reference letter would be forthcoming. Meagre paycheque in hand, I walked over to the MoneyMart and cashed it, stuffing the bills in my bag. My first job had lasted four days. I wandered the streets, depressed. Residential neighbourhoods morphed into a business district, but I barely noticed. They were just more buildings smelling of cement dust and the decayed detritus that gathered about their foundations. Tired and thirsty, I went into a convenience store for something to drink. The man ahead of me at the cash register was busily buying lotto tickets. I had heard of this back on the Island but had never seen the vast array of glittery choices that were available. How did they work? How do you choose? I leaned forward and paid closer attention to the transaction going on. Suddenly, the cashier whooped and yelled, “It’s a winner!” Everyone in the store cheered and the man ahead of me who had won turned around and hugged me. “How much?” he asked the cashier, breathless. The cashier held up a finger, the store hushed. He made a phone call, repeating the series of numbers on the ticket that the man had given him. The cashier’s face lit up in a huge smile while he scribbled something on a piece of paper and handed it to the man. The man in front of me closed his eyes for a moment, opened them, and read the number on the slip of paper. He began to sway, and I steadied him, getting close enough to glimpse the five figures on the paper. He had just won over eight thousand dollars. Wow. He began to hop from one foot to the other in a little jig. The patrons in the store cheered and danced along with him. I squeezed through the throng and escaped into the night air. I had never thought of gambling before but, tonight, it seemed like a good idea. Or a terrible one, a little voice whispered inside my head. I promised the little voice that I would only spend ten dollars. The little voice tried to say something else, but I quashed it. My city map had an assortment of businesses, restaurants, and places of entertainment advertised around its border. There was a small casino called Money for Nothing about a ten-minute walk from where I stood. Inspired by what I had just witnessed at the convenience store, I strode there in record time and entered the noise and the heat and the lights of my first gambling establishment. The ranks of slot machines were crowded with people. I continued past them and on to the gaming tables and observed the card games for a while. They didn’t seem very interesting to me. A great cheer arose from a different sort of table and I went to check it out. The roulette wheel was beautiful. The spinning and the bouncing marbles made it seem like a lot more fun than anything else I had seen so far. Excited, I exchanged my ten dollars for a coloured disc. I watched what the other players did and placed my disc on a number. The handsome young man in the tuxedo spun the wheel and the marbles flew. Around and around they went, making me dizzy. When they slowed and stopped, I stood there, mesmerised. The young man pushed a small stack of coloured disks towards me. I could only gather them and excuse myself. I had to pee. After I washed my hands, I dug the discs out of my pocket where I had stashed them. I couldn’t remember what each of the different colours was worth, but I had six of them. Feeling calmer, I returned to the table and placed two of them on a number. I won again! This time, I left all but the four I still had in my hand on the table. And won for the third time in a row. The table was beginning to attract more people as word spread―everyone wanted to be near a lucky streak. A little warning tendril crept up my spine, and, this time, I listened to my instincts. Gathering my winnings, I brought them to the cash window. The efficient man there counted, calculated, and extracted bills from a drawer. When he doled the money out to me, it took every ounce of my seventeen-year old restraint not to scream in victory. Instead, I carefully folded most of my twenty-seven hundred dollars and placed the money in a zippered section of my purse. I then hung the purse diagonally around my body with the main part of it snug to my belly and put my jacket on over top. I bought myself a celebratory bag of goodies and, luxury of luxuries, took a taxi back to my room. The next day, I rose early and walked in the direction of my former employment. I had decided that it would be better if my landlord thought I was still working. There was a coffee shop a few blocks further away and that is where I bought my first meal with cash money. I knew that if I kept this up, my winnings would be gone, and then what? While I sipped a second cup of coffee, I decided to make a list for myself. Jacinthe always teased me about my lists. “How can you need a list for stuff you do every day?” she would say. “Does it say it’s time to blow your nose? ‘Cuz you got a big booger in your left nostril.” Then she would laugh hysterically as I frantically searched for a tissue. The spasm that squeezed my heart left me breathless. Shaking, I put my coffee cup down. I was alone in a big, strange city with no friends and no family. There would be no Jacinthe walking through the door to sit with me and gossip about the other diners. I could just imagine what she would say about the cute guy at the counter. She would say, “That one needs a good seeing to. Look at the state of him!” I smiled as the first tear plopped onto my empty hand. The waitress was making the rounds with fresh coffee for her customers. I scrunched the napkin in my fist and blotted my face. This would never do. I flipped the paper place mat over and, when she arrived at my table, I asked her for more coffee and if she could lend me a pen. With a smile, she gave me both. There was a nice tip in her future―no need for a premonition to foresee that one. Shrugging off the memory of Jacinthe and all things Island, I started on my list. If I was to get and keep a job, or even have a decent conversation with anyone, the first thing I needed was some way to disguise my eyes. Of course, I had seen people wearing sunglasses, but they would be too dark and inappropriate for indoors. Maybe I could get regular glasses with a bit of a tint in the lenses but without a prescription. Should be easy enough. Secondly, and while I had a little time, I would gather information about how things work in a city―my ignorance was going to get me into trouble sooner rather than later. A Library would be a good, safe place to start. After that, well, it would depend on what I found out at the Library. I wrote down ‘write home’ as my third item and crossed it out; I wasn’t ready for that yet. With the five-dollar bill quite obvious on my table, the waitress was happy to point me in the direction of not one but two places that sold glasses. I smiled, squinting my eyes so she wouldn’t be frightened, and left. The glasses were easy, and it wouldn’t take me long to adjust to the grey shading. More importantly, they disguised my hazel eyes very well. It was like they disappeared. At home, we had a Library van that visited every few weeks. How could that have prepared me for my first experience at a city Library? Who knew there were so many books? At first, I just stood and looked at them, lined up side by side, row after row. I think I must have cried a little because one of the librarians asked if I was alright. I could only nod. I spent the rest of the day and part of the evening there, stepping out only for a bite to eat. The same librarian who had spoken to me earlier asked if I was finding what I needed. “I need to read everything,” I answered. Somewhat abashed at my outburst, I hoped I didn’t sound crazy, but she smiled. “Is this your first time in a big Library?” she asked. I nodded my head. “I’m nearly done my shift, but if you can come back about mid-morning tomorrow, I’ll show you around and explain how it’s organised.” “Really?” I whispered. She smiled. “See you then.” The next day, Moira toured me around each of the sections of the Library, which to my surprise included music, and introduced me to the Dewey Decimal Classification System. I was in heaven. When my very own Library card was placed in my hand, I felt happier than I had in a long time. The next few weeks passed in a glory of words and music. I couldn’t get enough. |