EXTRACT FOR

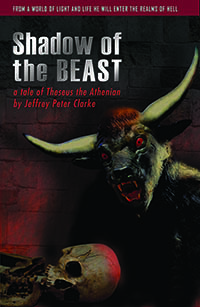

Shadow of The Beast

(Jeffrey Peter Clarke)

Chapter 1 - The BLACK SAIL

A clatter of

pottery bells broke the calm of a hot, pine-scented afternoon as the

mop-haired, bare-footed peasant boy in ragged linen kilt appeared over the rise

to hesitate for a moment against a boundless blue sky. Swishing his stick, he

called out to urge his small herd of bleating goats down the so familiar path.

To him the fates had allotted the tracks, the fields and the pinewoods as

compass of his days. Seldom did he find an opportunity to venture outside a

world bounded by the labours of each day. Yet when darkness came, even this

might become a forbidden realm. Through

clustered pine trees he now and then glimpsed the sea, a cauldron of liquid metal

above which hovered a lowering sun. Some way past the point where his path turned

inland the ground sloped away gently toward the southern end of a wide bay. The

boy stopped, not to rest, though his long day was coming to an end, but to gaze

out across the water with a hand raised to protect his eyes from the harsh

glare. Greeted by a welcoming sea breeze he remained a while longer, imagining

what wonders might be found beyond a distant horizon that was for him a place

of wild and youthful dreams. He would

have continued on his way except that below the horizon, almost lost amidst the

water’s dazzle, something moved as an insect crawling on beaten silver. It was

not, of course, the first vessel the boy had seen. Fishing boats plied the

waters daily, as did the larger boats from distant places; lands of hearsay,

lands people in the city talked about, lands he could never hope to know. To his keen

eye there was something different about this boat, though what it was he could

not be certain. Perhaps it was her steady progress - the progress of a larger

vessel. One thing he could be quite sure of, however; the now deserted bay

across which he gazed was her destination. He was also sure that the sun would

be kissing the horizon before she arrived at the meagre straggle of irregular

stone buildings that clung to the edge of the bay to form the small port of

Phaleron. Uppermost in his mind was the belief he and everyone in Athens and

hereabouts shared, that some day a ship would arrive bearing news of great

importance. An occasional comment overheard in the marketplace on those rare

visits to the city as well as remarks from the mouths of his own parents; these

had convinced him that this long-awaited vessel would eventually arrive. His

curiosity was much aroused. Could this be the one? As he

watched, a veil of cloud drifted across to haze the sun, so enabling him to

make out the ship in more detail. The boy peered harder into the distance then

letting out a whistle he threw aside his stick, gathered up his kilt and

started in haste along the path. The goats pranced then scattered aside to a

cacophony of bleating as he rushed headlong through their midst calling out,

‘I’ll be first to tell them! Yes, I will! I’ll be the first!’ The journey

would take him some time, bounding over rough, open pastures toward the

woodlands where the broader path leading from the harbour to Athens’ western

gate crossed open ground. His shadow dancing eagerly ahead, he would follow

this well-trodden route to the city. He would not reach the gate before the sun

went down but he would deliver his message before the boat arrived in the

harbour even though the wind at present looked to be in her favour. But if she

did not have a skilled Athenian crew, if she was one of those deep-keeled

Cretan vessels that could not easily be beached or would need to be moored at

the jetty in the dead of night, she might stand out in the bay until dawn for

safety’s sake, sheltered by the headland to her south. And what of the reward?

Yes, they had spoken of a reward for the one who brought first news of the

vessel. And it had to be the right vessel because the boy had abandoned his

flock and would otherwise be punished. It had to be the right vessel. Approaching

the city, he hurried on with shortening breath, passing by vineyards, olive

groves and orchards. On he went toward the massive double gate, on toward the

frowning stone tower of coarse Cyclopean blocks that it seemed only the

time-shrouded giants of old could have laboured to construct. Citizens and

traders were passing to and fro about their business, ignoring the wretched

beggars who squatted in the shadows. Oxen, asses and men hauled farm produce

and oil jars packed in straw to safety within the city wall, though on this

occasion there was little sign of the armed guards who were so often in

evidence. On he hurried through white-plastered timber dwellings that pressed

upon narrow, crowded streets, through the tantalising odour of cooking, through

the acrid smoke of forges until reaching the rough-hewn stairs carved into the

rock wall that wound upward to the acropolis. The boy stopped

long enough to calm his breathing then clambered nimbly, but was again quite

breathless by the time he reached the top. There he rested to gaze across the

open courtyard where arose the royal residence. This was the palace of Aegeus

the king, an imposing three storey, stone and timber building topped by a

palisade of stone-carved bulls’ horns. Glancing about, anxious in case someone

else should hurry past him to deliver the message first, he trotted across the

courtyard then scrambled awkwardly up the steps leading to the great,

bronze-clad doors of the main entrance. Almost there he was challenged by a

brusque, ‘Oi - where d’you think you’re off to?’ ‘I bring

news for our great King Aegeus!’ he yelled as the pair of burly, surly guards

with bronze-tipped spears and boiled hide corselets closed in to bar his

progress. The guards had found little to do that day other than pass time in

idle conversation. Here was something to break the monotony. Something trivial

but perhaps enough to offer modest entertainment. ‘What’s this

news you’ve got, then?’ one of the guards demanded, eyeing the bedraggled

intruder with an exaggerated frown that changed to a bristled, broken-toothed

grin as the boy peered up wide-eyed. ‘Well – what’s an urchin like you got to

say that could possibly interest Lord Aegeus?’ ‘There’s a

ship entering the bay,’ he blurted. ‘It’s a fine ship – not a fishing boat –

not a trader. It’s got a royal symbol on its sail.’ That was in

part true. There had been a device of some kind on the sail, but the vessel had

been too far out for even his keen eye to resolve it in detail. There was

something else, however - something the boy would not divulge to the guards in

case they dismissed him then themselves carried the news to the king. ‘What d’we

do with ’im?’ asked the second man, bringing his face close to the boy’s in

mock intimidation. ‘Chase the little bugger off do we?

The king might be takin’ ’is rest this time of the day.’ ‘Better

not,’ replied the first. ‘We’ve all ’eard about this ship people are supposed

to be lookin’ out for. Aegeus won’t thank us if it turns out the kid’s spotted

somethin’ important.’ ‘Nor will ’e

if it turns out we wasted ’is precious time,’ leered the other as they

continued to stare down at him. ‘If ’e’s having us on then ’e’ll get my boot up

his arse. Aye and ’e’ll leave ’ere a lot quicker than ’e arrived!’ Jumping up

and down with youthful impatience, the boy was tempted to dash by them. At last,

giving in to his urgently repeated pleas, they ushered him to the top of the

stairs then to the twin-columned portico, through the stout, copper-banded

timber doors and into a small, colonnaded courtyard from which other dimly lit,

frescoed passages led. As they crossed this, his enthusiasm began to wane.

Already daunted by the surroundings, he wondered how and by whom he would be

received. He was, after all, a humble, begrimed goatherd who, never having

entered this imposing structure, had only stood before it with the common

people to observe the occasional royal ceremony. Perhaps his sighting of the

ship would prove of no importance, perhaps his tale would be disbelieved. He

might face ridicule, or worse, a beating by the guards. At the far

side of the courtyard they passed into a gloomy antechamber lit only by small lamps

supported on slender metal stands. About the walls marched frescoed warriors

and beneath these stood tall, baked clay jars. For a fleeting moment, the boy

wished he could sneak away unseen, climb into one of the jars and hide until

the guards were gone. Now the strumming of a lyre reached his ear, now the

sound of voices. It was too late to run. He had heard

people speak of the megaron, the great hall, where Aegeus entertained and held

council, though no one he had met ever claimed to have entered it in person.

But no amount of hearsay could have prepared him for a sight that so cowed,

that so overwhelmed as he was conducted inside. He trembled with fear, wishing

only to be back in the fields with the goats he had so recklessly abandoned.

Before him were gathered more people than he could have reckoned three times

over on his grubby fingers; men, women, children, seated or standing in

conversation about the hall. At its centre lay a raised circular hearth inset

with small, multi-coloured tiles and almost as wide across as two men. Within

it, bright flames danced to cast wavering shadows about walls and ceiling. They

were shadows that lived - shadows of unearthly beings. Mingling with the smoke

was an odour of incense not at all to his liking. Afraid as the boy was, this

moment would remain in his mind forever. An alabaster

throne with tall, scalloped back stood at the far side of the hearth. On it,

cushioned by a lamb’s wool fleece, sat a gaunt faced man with well-trimmed

moustache and beard. His long fair hair was held in place by a headband of

gold-studded leather, his stooped form clothed in a belted white tunic of

finely embroidered linen. In his hand rested a goblet of beaten gold, newly

replenished by one of the female slaves who ladled from the wine jar carried

awkwardly between two of her male children. The boy knew

he was in the presence of King Aegeus, the man who ruled his land. Seated or

standing close by were the king’s richly attired kinsmen and companions, likewise attended by female slaves, whilst at the far side

of the hearth sat chattering the red-lipped noblewomen, their faces

white-glazed beneath long, elaborately crinkled hair. Adorned in

narrow-waisted, long, flounced dresses with short-sleeved bodice cut away to

leave their rouged breasts exposed, they were bejewelled in a manner the boy

found incomprehensible. First to

notice him enter with the two guards had been three courtly-dressed children

who stood chattering among themselves close by. They made no effort to convey

their observation to anyone else but continued as before with frequent glances

at the newcomer who felt utterly crushed in the presence of such opulence. The

strumming continued and he saw that it came from the hands of a grey-haired,

almost toothless, long-bearded old man in blue tunic who sat to the king’s left

and whose attention he held. From time to time the player raised a hand from

the lyre in order to recite in deep, sonorous tones the verses of some ancient

epic whose meaning was totally lost on the boy. Perhaps nobody would

acknowledge his presence until the bard had finished. Staring

about the hall, he was awed by the upward tapering, russet-painted columns that

supported a heavily beamed ceiling, this latter blackened by years of rising

smoke. About the walls, alternating with bronze-tipped spears, hung

boiled-hide, metal-edged shields, some light and circular, hardly an arm’s

length across, others almost as tall as a man. All were gilded, all elaborately

decorated. Here was something the boy found reassuringly familiar. Much plainer

versions of these shields he had seen borne by men passing to and from the city

on those occasions when the drums of war caused him and his family to gather

their livestock and retreat within the sanctuary of Athens’ defensive wall or

to the more distant rural sanctuary of their kinfolk. It was the

lyre player who next noticed the boy. Finishing his verse, he laid aside his

instrument and indicated to Aegeus that a stranger awaited his attention. The

king and those about him turned aside as one of the guards stepped forward,

bowed and announced above a descending silence, ‘Lord Aegeus, we beg

forgiveness at our intrusion, but this boy says ’e’s observed a ship. He says

it’s got a royal device on its sail.’ ‘Does he

indeed,’ replied Aegeus, rising slowly from his throne to approach the boy. Shaking

visibly, the goatherd fell to his knees, stared hard at the floor and

stammered, ‘N-noble king, I saw – saw it – yes. A ship with – with -.’ Aegeus

peered down at him to ask solemnly, ‘It bore a device, you say - what device?

And what else? Did you see the colour of the sail?’ ‘I did,

mightiness, yes,’ replied the boy at last summoning enough courage to look

upward into the king’s eyes; eyes that spoke of more than just weariness. ‘I saw

it clearly, sire. The device was a – a -.’ ‘A double

axe?’ interjected the king. ‘Yes, lord,

that’s what it was - a double axe.’ This statement was a guess but probably, or

so he hoped, not a bad one. As for the second there was no doubt at all as he exclaimed,

‘And the sail, master – the sail was black!’ Aegeus did

not at first respond, though several of those close to him nodded their heads

glumly then fixed their gaze upon the stone floor. The silence, growing more

profound, was broken by wood spitting from the fire then by one of the children

coughing. Tension grew as Aegeus continued to stare down at the boy, who in

turn began to fidget uncontrollably. When the

king at last spoke, his voice was bland in the manner of one whose emotions,

whilst kindled, must at all costs conceal his true feelings, though his

expression was clouded with pain. ‘A black sail. Very well. When what you tell

us is confirmed, you shall have the promised reward. No doubt it will change

your life as your message is to change mine.’ Bidding the boy rise, he turned

to the gathering then declared, ‘Our entertainment is ended. There are other

matters to which I must attend.’ Their heads

bowed, people began to leave, glancing at Aegeus in sympathy or not looking at

him at all. Saying nothing to him or to one another. Some of the women wept as

they followed the men. As he, too, was ushered from the hall, the boy turned to

see Aegeus in the act of instructing a young slave boy who, no doubt, would run

to the headland then report back to him over the ship. The king, stooped as if

carrying an invisible burden about his shoulders then walked slowly,

accompanied by his aged lyre player, toward a door at the far side where both

vanished into darkness. The boy was taken to wait in the anteroom. The great

hall was deserted. In the fire within the circle, logs settled, life breathed.

In the embers eyes watched. In the smoke whispers gathered. Emerging from gaps

in the floor close by the hearth, black beetles stole about the deity of heat

that was the centre of a realm they could for a time claim as their own. *** Oil lamps on

stands of twisted bronze cast a feeble light over the stone walls. Aegeus sat

in pensive quiet. The air hung close and oppressive. Nearby waited the old man,

his lyre propped by the side of his chair. When the king at last spoke, his was

a voice of sad resignation. ‘Haemon, my

dear friend, we need not await confirmation of the sail. A simple goatherd

would not make such a statement if it were false since he would not know its

meaning. Theseus, my son, did not survive the ordeal. Those hopes I held for

our future are scattered as chaff to the wind.’ The old man

said nothing as Aegeus continued. ‘He was the staunchest champion of our land.

He shone as the brightest star in our heavens. Now, that light is extinguished,

and we are condemned to darkness as are the blind.’ ‘He should

never have sailed to Crete,’ muttered the lyre player. ‘I should have tried to

persuade him. I failed you in not doing so.’ ‘Ah,’ sighed

Aegeus, ‘I doubt the gods themselves could have prevented his making the

journey there - I certainly could not. He would often listen to you when he

dismissed the advice of others as a passing breeze but this time he was beyond

persuasion. Perhaps he saw glory in that venture though no man could ever claim

he was tainted by vanity or greed.’ ‘He was

burdened by neither,’ agreed Haemon. ‘But I say again, had I tried to stop him

joining the rest when the envoys came, perhaps he would be here with us now.’ Aegeus rose

up and turned to face the window, saying, ‘No, had he stayed when others were

sent out to confront unknown danger, he could never have lived with himself.

Now the people look at me in anger for allowing him to go on that final voyage.

The anger of some will turn to hatred when they learn he has shared the fate of

those young people of ours who sailed to Crete before him. Yet I thought that

he of all people might have – no, the will of the gods has prevailed. And still

my so-called brother Pallas waits in the south and will not rest until Athens

writhes defeated in his grasp. My son would have stood against him. By the

light of his valour Theseus would have driven back the shadows cast by Pallas.

Once news of the ship reaches Pallas’ ears, he will uncover the chalice of

poison he has been fermenting.’ Turning once more to Haemon he declared, ‘It is

a poison for which we have no antidote, my friend. There are no strong allies

on whom we can call. There is no man in the city who might rally the people

sufficiently to prevail against our enemy. Metion, the captain of my palace

guard would gather his men to Athens’ cause but great a warrior though he is,

he does not possess those other skills needed to capture the hearts of the

people. He is at the forefront in battle but sets himself aside in times of

peace.’ ‘Lord

Aegeus!’ responded the old man, standing up quickly despite his aching bones.

‘Why do we not send over the water to Troizen? King Pittheus surely would cross

the gulf to stand with us. He has every reason to despise Pallas.’ ‘Pittheus,’

sighed the king, ‘is too busy watching his own back. He will not dare leave

Troizen, not until matters are settled there. Pallas controls the supply of

silver from the mines at Laurion and together with Cretan gold uses it now to

fund intrigues at Troizen just as he has in the past here in Athens.’ Aegeus

relapsed into pensive silence. Eventually

Haemon asked, ‘Shall I call for wine?’ ‘No – no

more wine,’ breathed Aegeus. ‘My grief would sail large even on a sea of wine.’

Aegeus sighed, pressed hands to his face then fixed his gaze on the window

whose leather blind was held rolled up above. The sky was darkening. ‘Just now,

my friend, I would prefer to be alone.’ Haemon got

up, stepped to the door but turned briefly with a tear in his eye as Aegeus

added, ‘Whatever happens, never doubt that any man could have a truer friend

than you have been to your king.’ The old man

left but crossing the great hall in near darkness to the echo of his own

footsteps he hesitated as if about to retrace his steps, shook his head, then

continued on. Aegeus sat

in silence. The first stars would soon begin to appear as he gazed out at the

sky, and with those stars would return memories of the long life he had lived

and his term of kingship in Athens. |