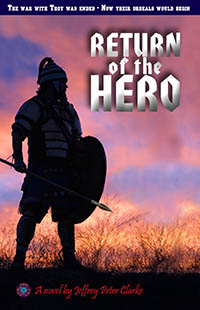

EXTRACT FOR

Return of The Hero

(Jeffrey Peter Clarke)

Prologue

The city burned,

abandoned by the gods. Angry flames clawed skyward from the citadel and lower

town. Dark smoke spread above sombre ruination – rising as a vast and ravenous

beast to gloat over its prey. It billowed through shattered walls. It cast

baleful shadows over mid-morning countryside. White-haired Priam, their aged

king, was slain, his head struck off by the blow of an enemy sword. Those

people of Troy not killed or taken as slaves wandered defeated and dispossessed

through the blood-defiled streets of their once proud city. The dogs whimpered

mournfully at their heels as they drifted back and forth, hoping to glean from

the destruction whatever the now departed enemy and fate had left them. The conquerors had sailed with the

rising sun, welcomed into the purifying realms of a bright sea, their vessels

containing treasures from palace and shrine, and those women and children they

thought it worth carrying away to captivity. It had been a disordered, an

ill-disciplined conflict: many heroes had fallen broken and bleeding to cold

earth. Many warriors had been stricken from the ranks of both sides before the

ten years siege had ended. Even Achilles, champion and slayer of men, had

perished, victim of an arrow shot by accursed Paris, son of Priam. But the great leaders of the Achaean

Greeks, the victors of this bloody contest, were with their men: Agamemnon,

famed king of Mycenae and leader of the expedition, his brother, Menelaus, king

of Sparta, the abduction of whose wife, Helen, had been the kindling of a war

already destined to ignite. With them, too, was Nestor the elder, king of Pylos

and wise council to others – and Odysseus, lord of Ithaca, the man whose wiles,

whose conception of the wooden horse, had in the end resulted in the crushing

of their enemy. They sailed with pennants flying, each

group of vessels under its own leader, each group in sight of the other. But

with land now vanished below the horizon the gods proved fickle. Before night

closed over their diminished fleet, sombre clouds billowed to sweep threatening

low across the sky. Glimmers amidst the darkness became raging flares, the

primordial growl of thunder grew louder and the raging beasts of the sea arose,

threatening to devour them. Vessels heaved, shuddered and rolled, shrouded in

hard-driven spray as sails tore asunder and timbers screeched agony. This was a

storm raised to crush their puny hulls. A storm to hold wretched humanity in

utter contempt. Many among their crews believed it was sent by Poseidon to avenge the sacking of Troy in spite of that

god’s earlier favouring of the Greeks. They cried out to Poseidon and to Zeus,

their pitiful voices damned to the chaos of wind and a sea they dreaded was

soon to possess them. Long before sunrise the storm had

passed, the sea had calmed and with morning light the fleet began to regroup.

From each contingent there were losses, though none as great as had been

feared. Throughout that fresher, sunlit day, with sail and hard-worked oarsman,

the scattered ships re-joined their leaders and made good where possible the

damage inflicted upon timber and rigging. But there was one contingent missing,

that of Ithaca, and though they scoured the horizons, Odysseus’ vessels were

nowhere to be seen. Chapter 1 - Telemachus

Under tranquil skies

they fought a bloodless contest. Sword clashed with sword and sword with

shield. The air shivered with ringing bronze under the blaze of a late morning

sun. Telemachus parried and lunged, swinging blade and countering with shield,

entwined in whirlwind dance with his two contestants as five other men of the palace

guard, also armed for combat, looked on in judgement. The contest ceased.

Gasping, laughing, clattering down weapon and shield to the dust, wiping sweat

from their brows, each congratulated the other. The two men stooped to regain

their breath and the third man swayed back, panting hard. ‘You’ll more than

stand your ground with any man, young master!’ declared an onlooker with fist

raised. ‘Aye with any two

I’ll wager,’ agreed Thoas, captain of the men with whom Telemachus, prince of

the royal house of Ithaca, trained in arms. ‘Then we’ll call it a

day,’ responded Telemachus, lifting off his ornate bronze helmet then stepping

aside to pick up and sheathe his blade. The men relaxed and

spent time in discussing among themselves, with appropriate gestures, the

death-dealing techniques of armed combat. Telemachus glanced at the high wooden

enclosure surrounding them, at the hills rising beyond then at the door

opposite, presently barred. Close by it arose a post from which was suspended

the carcase of a pig, focus of their contest earlier in the day when the sun

was newly risen. They approached this and wrenched from it those spears that

had found their target in its flesh only to disturb a shimmering mass of flies

that burst away into the air. There, too, were those shafts that had passed

close but either lay on the dusty ground beyond or stood impaled in the timbers

of the compound. ‘Has no one yet questioned

our presence here?’ Telemachus asked, gulping spring water from a leather

flask. ‘No one,’ replied

Thoas. ‘We’re off the beaten track and away from farmland. And if they did I’d

tell ’em the truth of it, that a small number of us want to practise our

fighting skills undisturbed – except that I’d not mention your being here with

us, of course.’ ‘Of course,’ breathed

Telemachus, adding, ‘then I’ll make my way back as usual from a different

direction to that of our men. Then we’ll meet another day, soon.’ ‘Whenever it suits

you, young master,’ nodded Thoas. ‘Your time’s been well spent. Yes, well spent

indeed and I’ll not say that out of deference though I may boast many years of

experience.’ As Telemachus strode

away to unlatch the gate one of the men turned to Thoas, ‘He handles sword and

spear mighty well – mighty well, as a seasoned warrior should.’ ‘There’s a grim

determination in him; anyone can see that,’ remarked a second man. ‘I see it in

his eyes, I see a born killer. He doesn’t waste his energy – no, he calculates

and when he meets his man in battle he’ll judge that vital instant to strike.

For a moment back then I feared he might forget this is only drill and really

cut me down.’ ‘I’ll say one thing,

though,’ added the first. ‘Aye, and what’s

that?’ asked Thoas. ‘He’s yet to face a

man set on killing him.’ ‘True enough,’

responded Thoas, eyeing the gate through which Telemachus had made his exit,

‘and the way I see it that day may not be far off.’ *** At the centre of the

megaron, the great shadow-laden hall where a king once held court, a fire

glimmered in the circular stone hearth. Wood settled to breathe a sigh of

memories. Smoke drifted, mingling with the fragrance arising from incense pots

set about the room on small bronze stands. It swirled in phantom wisps past

high windows where the sky had darkened then to vanish amidst soot-blackened

beams. Firebrands were mounted high at

intervals along the walls where they added a mellow shimmer to the interior.

Their light glinted from the grim tools of combat mounted in between; bronze

swords, spears and double-headed axes long ago placed on display between heavy,

figure-of-eight shields. Ranged beneath these at ground level ran a fresco of

prancing, stark-eyed warriors in plumed helmets, shields protecting their

sides. Their spears were poised high, ready to hurl. In the sanguine glow they

shivered life as if about to career along the walls and strike down their

enemy. Gone were the

breezily chattering, bare-breasted female courtesans in their gaudily flounced,

flagstone-sweeping skirts, the importance of their kind much diminished since the

days of Odysseus. Gone also the handful of younger men who waited dutifully to

serve those pampered butterflies through largely uneventful days. Gone the mop-headed

slave boys and with them the plainly attired, straggle-haired serving girls.

Absent, too, was Phemios, aged bard whose tuneful lyre and wistful, mellow

singing evoked memories of happier days in what had over recent years become a

place of melancholy brooding. Shades of a glorious past hovered in dark corners

and lingered amidst the columns where the light of the firebrands did not

penetrate. There were only two people within the

great hall. Penelope, a slim, pale figure whose honey-pale hair spilled over

the shoulders of a richly embroidered gown, sat upon patterned cushions placed

there as a concession to material comfort. The throne she occupied was carved

from pale limestone with a high scalloped back and, with wooden seats close by,

was positioned between two of the russet-hued, downward tapering columns that

supported roof beams high above. By her side stood young, dark-eyed Niobe, the

slave girl of her choice. Lost in thought Penelope gazed at the whispering fire

whilst the girl caressed her mistress’ hair with an ornate, gold-inlaid comb of

precious ebony. Niobe sang with soft and comforting words at her mistress’

delicate ear. The throne had once belonged to

Odysseus, warrior-king of rugged Ithaca and the islands thereabout. Agamemnon

had returned with Trojan loot to Mycenae, wealthiest of the Greek cities. On

stepping ashore he had sent out messengers to announce their victory. He had

entered the citadel to the sound of blaring horns, passing beneath the

monumental gate set into massive walls and topped by rampant stone lions. A

great triumph was his - but Agamemnon had dismissed the prophesies of Priam’s

daughter, beautiful Cassandra, who had been abducted by him and brought to

Mycenae. She had warned him of the fate he was soon to meet but, cursed by

Apollo, her prophesies were forever to be dismissed as false. Ten years had passed

since the return of Agamemnon to Mycenae but still Penelope waited for her

husband. Eyes lightly closed Penelope savoured the girl’s attentions. The comb

slipped with sensual touch through her hair. Niobe’s other hand fell to her

mistress’ breast, teasing gently through the fabric of the gown. Penelope

slipped an arm around the girl’s waist, drawing her closer, feeling the heat of

her lithe young body. Niobe’s breath, a flame of passion, burned her cheek.

Niobe’s lips brushed her ear as fire-moths from the secret realms of night. Her

lips parted but no words came as she peered into the girl’s eyes. Unwelcome sounds! The

chatter of servants and slaves making ready the nightly feast echoed along the

short corridor passing from the megaron to a flight of steps that gave access

to one end of the dining hall. Before long her suitors would begin to arrive

from Ithaca’s taverns and lodgings, as always expecting food and drink. As

always calling for her presence. More insistent of late, demanding an answer to

their question: who among them would she accept as her husband? Which of them

would gain the throne and possessions of Odysseus and achieve domination over

Ithaca’s island kingdom? Penelope had until now kept them at bay through the

backing of her modest palace guard, through her willpower and her cunning. For

a while longer her cares would be allayed by the beguiling touch of Niobe.

Penelope closed her eyes once more and drifted into rare contentment. The scuff of sandals on flagstones

invaded her reverie. The girl’s hand slipped away but the comb maintained its

soothing glide. From the gloom of the corridor entrance to her left a figure in

pale tunic approached with confident stride, short sword in gilded scabbard at

his side. Clean-shaven, sharp-eyed, his fair, shoulder-brushing hair circled by

a turquoise and gold band, he was slim and well-built as any well-bred youth of

his age. His voice rang bold and clear through the hall. ‘Mother, here you are

and looking regal as ever!’ Penelope eased back the hand holding

the comb. ‘Niobe, you may leave us now.’ The girl stepped away but as she

vanished into the gloom of the colonnade behind the throne she glanced over her

shoulder at Telemachus, a mischievous grin touching her face. With his mother’s

attentive eye on him, Telemachus thought it better not to acknowledge Niobe’s

smile. ‘Telemachus!’ his mother demanded.

‘Where have you been these last two days? Penelope had for too long regarded her

son as a vulnerable boy. Since holding him at her breast she had desired only

to protect him, realizing later that in so doing she had risked making him more

vulnerable still. These last few years much about him had changed. It encouraged

but at the same time unsettled her deeply. Grinning broadly, Telemachus leaned

against a column. ‘Oh, out and about the country as usual.’ ‘Well stay clear of those men once

they start drinking. How many times have I warned you?’ ‘I long ago lost count,’ Telemachus

replied, ‘but your fretting will help neither of us.’ He moved to stand

directly before her. ‘There’s something I have to tell you but before that,

when d’you plan to end this farce with the shroud. Our situation is changing

for the worse as you are well aware.’ ‘I well know that,’ she sighed,

pressing hands against her pale cheeks. ‘And you surely appreciate why I spend

the time I do at the loom. “This farce with the shroud,” you choose to call it

- I determined I would weave a shroud for Laertes, Odysseus’ father, your

grandfather. I have made it clear - I’ll make no decision over marriage until

the shroud is completed. It is an accepted part of -.’ ‘All your suitors

must have guessed by now,’ he interrupted, ‘even those with the brains of a goat,

that you have no intention of completing the thing!’ He gazed about the hall

then added, ‘You began it over two years ago and you undo much of what you’ve

woven during the day so you have to begin again next morning. It speaks only of

desperation. As for Laertes – I encounter his men in the marketplace and they

assure me he works his farm as a man should and so far has shown no sign of

dying, though I understand his health has never been strong.’ ‘Well, dear,’ she replied, her face

wrinkling with a forced smile, ‘the “thing” as you choose to call it has helped

us keep those men at bay a while longer. Even they have some respect for

our customs and that’s all that matters at present. And – and, Telemachus, you

ought not to be spying on me.’ ‘I haven’t been

spying on you,’ he responded. ‘And as for customs - those men have tolerated

what you’re doing because it’s suited them to fatten their stomachs at our

expense for the best part of seven years. They’re convinced my father’s bones

lie rotting in some foreign land and I can’t argue with that since we have no

idea whatsoever what became of him.’ ‘They cannot know his fate!’ she

snapped, then closed her eyes adding quietly, ‘And nor can you, Telemachus. No

- nor can you.’ ‘Mother, he sailed

for Troy when you were a girl of seventeen. He’s been absent for all the years

I’ve lived! You and others describe him as a brave warrior but some say he took

too many ill-considered risks and maybe one day the gods turned against him. We

drift in an ocean of hearsay and I seek only a rock of truth.’ ‘Make of idle talk what you like,’ she

countered angrily, ‘but he will return! I know he will! I feel

his spirit amidst the shadows when I sit here alone. I offer prayers daily to

the gods – to Athena, yes, and to Zeus himself. And the oracles - they say he

will return to Ithaca. Before he set foot in Mycenae, Agamemnon sent word to

say your father had departed Troy with his ships and their crews in good

spirits. King Nestor reported it also.’ ‘Fine,’ shrugged Telemachus, ‘but both

of them sailed straight home. No one can say what happened after that.’ ‘Perhaps not!’ she responded, her

knuckles clenched white, ‘but there have been rumours over the years from

travellers abroad who tell of his being seen. Don’t you listen to what these

people say?’ ‘Hardly ever! Rumours

are like wild birds; they arrive from nowhere, they

alight anywhere and everywhere and then they’re gone. As for the oracles, they

tell you only what you want to hear. Truth is no woman in any land of the

Greeks ever held a king’s authority. Other rulers no longer correspond with you

and because of it I know far less than I ought of what happened after Troy. I

should by now occupy the throne of Ithaca but you contrived to prevent it over

the years and to my shame it suited me to accept this longer than I ought.’ ‘Yes,’ she glared,

twining and untwining her fingers, ‘I contrived to prevent it! Whichever of

those men took me in marriage would expect his own heir to gain your father’s

throne after him. They’d assume you would raise support from among our people

and try to claim your inheritance by force. If I’d stood down before you

reached manhood you’d have been dragged away in the night and I’d have seen no

more of you – not even your ashes!’ She watched in charged silence as

Telemachus strode around the hearth to gaze up at those hanging weapons

untouched even in the days of his father. As a child he had employed their

harmless wooden copies to engage in combat with others of his age but even then

he would never accept defeat. He returned to face her, saying,

‘People ask why Thoas and our guards do nothing when those men enter the dining

hall to live it up at the expense of our treasury – my inheritance. I

know a good few of them by the sound of their belching in the evening and the

sight of their vomit on our flagstones before the slaves clean it up. There

were only a handful of them to begin with and they actually brought gifts until

the likes of Antinous and Eurymachus came along and disowned the rules of

hospitality, though I - I confess I did drink with them on occasion.’ ‘Yes and you were

invited only so they could keep an eye on you. Thoas and his men ensure they

stay away from me and away from our private chambers. And when your father

returns he will see how I and those who remain close to us have kept his

affairs in good order.’ ‘Really!’ responded

Telemachus. ‘Have you seen an account of our stores recently? No, you leave

such matters to poor Euryclea who has no wish to cause you further anxiety and

therefore says nothing. I frequently go into the vaults to check things.

Through the demands of others our gold and our silver are diminishing of late

quicker than they can be replenished in spite of a healthy trade, as are our

oils, our wines and much else. I find the palace guard are costing us more in

silver for their loyalty than they ought and as for Thoas himself – I think

it’s more than the occasional gift of silver that’s kept him on our side.’ ‘Just - just what do

you mean by that?’ she demanded with fist-clenching anger. ‘Mother,’ he replied,

‘I’ve seen Thoas enter your chamber during the night and I’ve overheard remarks

from our servants. Your liaison is no secret. They also comment on that slave

girl of yours who’s often in your chamber until dawn.’ ‘Telemachus!’ she

snapped, rising abruptly to her feet. ‘You’ve said enough and, yes, you have

been spying on me! This – this is not easy.’ Penelope fell back onto her

cushions with a pitiful sigh then added, ‘I have always done what I must to

help preserve your life.’ ‘If any man, if

Antinous, Eurymachus or any of them offer me challenge,’ Telemachus declared,

‘I’ll gladly take him on.’ ‘Telemachus, no! Do

not provoke any of them - especially Antinous! I recall seeing him slip an arm

about your shoulder as if you were one of his own kin. That man would just as

easily thrust a knife between your ribs and he’d still be smiling. He considers

himself first in line to your father’s throne regardless of what the rest may

think. He’s a true son of that upstart they call “The ox-eater,” that awful man

who imagined himself another Heracles. Your father put him down by force of

arms when he rebelled and because of it he refused to go with the rest of our

men to Troy. Nothing would give him greater pleasure than to have his only son

take possession of our kingdom.’ ‘I know what Antinous

and some of them are capable of,’ responded Telemachus, calmly. ‘As for his

father - merchants who’ve had dealings with the so-called ox-eater say he’s

grown fat as an ox himself through idleness and a surfeit of wine.’ Penelope relaxed into

her cushions. ‘At least you show less interest in the wine flagon than you once

did, if not the blatant come hither looks of our serving girls – especially

Niobe. I note her expression whenever your name is mentioned. Oh, I ought not

to blame you, dear - it’s only natural at your age.’ Telemachus rose from

the seat. ‘Yes and as you’re well aware I train hard with Thoas and those men

closest to him - and I do mean hard! I insist he treats me as he would any

freeborn man expected to defend what’s left of our kingdom and believe me I

will.’ She gazed at him anew

and saw before her a young warrior, a flame that might illuminate her life as

his father once had. ‘I hear comments over how fit and strong you appear. I

overheard someone compare you with Apollo who slew the arrogant and unjust with

his arrows.’ ‘Then I’ll

concentrate more on my target practice,’ he grinned. ‘And have no worries over

my working with Thoas; we never refer to your affairs or those of the

palace.’ ‘How very thoughtful of you, dear,’

she mused. Telemachus stepped

closer, saying, ‘Now I must tell you: Three days ago I spotted a stranger

loitering close by. I took him to be a merchant so I went over to question him

in case he wished to trade with us. His name was Mentes. He claimed he was a

captain of the Taphians and so I -.’ ‘The Taphians!’ cut

in Penelope. ‘They’re little better than pirates!’ She drew her breath then

added, ‘Well - they do on occasion supply our workshops with copper and tin -

probably stolen from other traders.’ From the direction of

the dining hall came shouting, thudding benches and a surge of raucous

laughter. Penelope glanced uneasily aside. Telemachus ignored

the disturbance then continued, ‘Pirate or no, the Taphian recognised me

because he’d had dealings with the old man before he sailed off to Troy and

seemed to think highly of him. He’d been trading along the coast of Africa for

many years and was unaware until arriving on Ithaca that my father had

disappeared. He’d overheard your suitors’ conversations in the taverns when

their tongues were loosened with wine and realised what was going on. I offered

him wine and gifts but he declined these because he was pressed to quit our

shores that morning. He offered advice I consider worth following.’ ‘Advice from a

Taphian?’ she responded. ‘Need I call for strong wine before you go on?’ ‘No, mother; perhaps

later. He suggested I summon a council of our citizens to demand your suitors

return to their estates so we can be free of them. I understand such things

were done in my father’s day: it may work now.’ ‘A council of our

citizens!’ she exclaimed, rising once more from the throne. ‘You imagine our

problems can so easily be solved? There’s been no such assembly called since

the victory over Troy was announced because it would be unacceptable for me, a

mere woman, to do so. Councils meant something in your father’s

day but I doubt they would now. And how much notice d’you imagine those

thirty and more suitors and their hangers-on, yes, over a hundred all told,

will take of farmers, craftsmen and traders even if they were outnumbered ten

to one? Many among them once subject to your father’s rule have since become

independent men of wealth. They look upon our citizens, our artisans and our

farmers much as they do their own peasants.’ ‘Men of wealth you

say,’ responded Telemachus. ‘Well I’m informed a number of their menials were

spotted making off with some of our livestock only three days ago. Did you know

of this?’ ‘Yes,’ she sighed, ‘I

– I was informed of the thefts. They’re hoping Thoas’ men will ride out on patrol

and leave the palace unguarded.’ ‘Thoas’ men will

remain here whatever happens outside the city wall,’ Telemachus assured her.

‘Thefts or no - I have seen to that.’ There was further

commotion from the dining hall. Penelope glanced aside, saying, ‘If they

thought our people might take up arms against them they’d summon help from

beyond Ithaca. We’d need the gods themselves on our side as well as the palace

guard but the gods have taken precious little notice these past years. If it

wasn’t for the oracles I don’t know what I’d –.’ ‘Never mind the

oracles!’ he cut in. ‘Tomorrow morning I’ll have our slaves go out with rams’

horns. I’ll have our free men gather in the marketplace before the suitors

arrive. It may still help matters if we’re seen to retain the backing of our

citizens.’ She was considering

his words when Medon, a wiry, kilted, shaven-headed elderly male of North

African aspect entered the hall. Though a slave of Odysseus’ house the suitors

had requisitioned him to act as their messenger. They had forced him with

threats of humiliation, often violence, to carry a twisted wooden cane intended

to mock the gilded staff traditionally carried by palace heralds. ‘My Lady,’ he

announced, pausing to bow at a respectful distance, ‘food and wine are prepared

and those men are demanding your presence.’ ‘I’ll do so when I’m

ready,’ she replied tersely, adding under her breath, ‘Before their manners are

dissolved by a surfeit of wine.’ As Medon left, she placed a hand on

Telemachus’ cheek. ‘For my sake, for the sake of your father’s house do not

give those men cause to act against us - against you.’ ‘Our people will lose

whatever faith they still have in the House of Odysseus if I continue to do

nothing,’ responded Telemachus, lifting her hand away. Penelope clasped her

hands together and gazed into his eyes. ‘Then do as you please, my darling. I

will sacrifice again to Athena. I will beg the gods to protect you if only they

will listen. Now I must go and face those men again.’ Her gown sweeping

behind, his mother stepped away in the direction taken earlier by Niobe. Her routine was well

established. She would ascend to her chamber and prepare herself for confrontation

before treading the narrow, windowless passage and dark steps down to the

dining hall; steps once used by Odysseus and his queen to access the hall

directly from their private rooms. There she would unbolt and pull inward the

heavy wooden door. There she would stand to face her suitors at the base of the

low steps beneath the colonnade supporting the gallery above. She would gaze

across the dining hall in dignified silence. She would listen to their comments

and their demands then inform them in as clear and calm a manner as she was

able, ‘I hear what you ask but I cannot yet make my decision.’ There would be

murmuring and crass remarks but if wine had already loosened their tongues to

expose their truer, baser selves she would turn away without speaking, bolt the

door and retreat to her room. The palace contained a number of such passages, some

never used, dim and forbidding, a world apart, their purpose long forgotten. As

a boy Telemachus had found adventure in exploring with a firebrand to discover

the secrets he imagined they must contain, often alone because he had no

brother or sister with whom to share his adventures. He was aware of the

babble and the odour of food drifting in from the dining hall. When the noise

subsided he listened for his mother’s voice but if she spoke too softly it

would not carry back to the megaron. He stepped up to the throne and, for the

first time since those playful days of childhood, he sat where his father had

sat amidst the colourful opulence and lively company of his courtiers. Smoke from the hearth

arose in spectral coils. A brooding stillness pervaded the great hall. In that

twilight void he gazed across columns and shadowed walls. His attention fixed

upon the man-killing weapons placed there long before the days of his father.

The glow of firebrands shimmered upon polished metal and it seemed the painted

figures below quivered with hidden energy. The air stirred and in his mind the

warriors gathered with spears raised high. There Telemachus gave voice to his

thoughts, ‘For too long others have defiled my house. Whether he lives or not,

my father’s kingdom will never be theirs. As Zeus stands large above our world,

I will not let that happen!’ |