EXTRACT FOR

AKWESASNE

(Ernest R. Rugenstein)

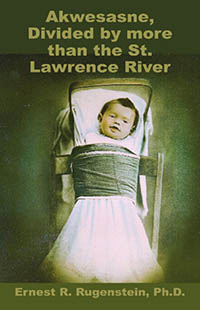

BOOK DEDICATIONThis book is dedicated to Esther M.

Bonaparte. The picture on the front cover is her christening day photograph.

She was born October 24, 1914, to Agnes Cree and Frank Cook of Akwesasne. The

picture is exemplary of the dichotomy she grew up with. She is dressed in her

Roman Catholic christening gown and swaddled on a Native cradleboard. It shows

her growing up in “Mohawk” culture and living in an English world. At one point

in her life, she married a white man but

never was seen equal to whites. She was a member of the St. Lucy's Catholic

Church in Syracuse, NY and a member of the Kateri Tekawitha

Circle. Additionally, she was a founding member of the North American Indian

Club of Syracuse On October 9, 2005, Esther Margaret Bonaparte passed away at the age of 90 years

old. Her children include Joyce (the late

Richard) Kelso of Ogdensburg, Honora Anne Bonaparte, Gary (Jessica) Bonaparte

of Syracuse, Sheree Peachy (Richard Skidders) Bonaparte, Tami Bonaparte of

Akwesasne and daughter in-law, Helen Falcone. Loving grandmother of Keli, Rick,

Arron, Jason, Erich, Cheavee, Tasha, Tara, Ahtkwiroton, Stephanie, Ietsistohkwaroroks,

Matthew, Ciele, Konwahontsiawi,

Karonhiotha, Adam, Zoo, DonJon,

Iaonhawinon, Tehrenhniserakhas,

Taylor, Ienonkwatsheriiostha, Colton, Cheya, Sako. Ella, Marcey, Elcey, Jasper, Maverick,

Darryl, and Havoc; and 23 great-grandchildren. She is survived by many nieces,

nephews, relatives, and friends.

Predeceased by her husband, Hubert Bonaparte and former husband, William Brenno; two sons, Allen and John Bonaparte; one grandson,

Daryl Bonaparte; one granddaughter, Katsi-bear; five

sisters, Louise Bigtree, Theresa Cree, Mae Syron, Harriett Sielawa and Ann

Barnes; one brother, and Tom Cook. One

last important note, Esther was an avid New York Yankee Fan! PREFACEAs I was preparing to write my dissertation

there were two areas I was interested in. One

was the minority population of Germans living in Poland after World War Two,

the other was the Mohawks of Akwesasne

and their interaction with the federal governments that surround them. The thrust of this book is one close to my

heart. It comes from a combination of being a Cultural Historian, the fact that

my wife and her extended family are Mohawk with many still living at Akwesasne,

and finally my affinity for those cultures being oppressed by more powerful

cultures. I have always loved history even at a young

age and I think it’s because I like stories. Many times, I encounter students

that will tell me, “they don’t like history,” or that it’s “boring.” I tell them that history is just that, a

story. As in any account of any story, there are main characters, plots and

sub-plots, and in most cases the perception of good and bad. The history of the

division at Akwesasne is such a story. I have a deep interest in the history of

different cultures. In particular, the

minority culture that is enveloped within a major culture. In 1989-1990 my family and I were living

outside Ogdensburg, NY. The conflicts occurring at Akwesasne consumed the

interest of everyone in the North Country. Roads had to be blocked and detours

were needed to get from Massena to Malone, NY. My wife’s extended family, being

from Akwesasne gave me a unique insight

into the impact of the event. The occurrences were discussed at the time with

family members who often spoke about the effect it had on families on and off

the reservation. Part of my family was involved

also. My sister used to charter tours with Peter

Pan Bus Lines from Rochester, NY to the Mohawk

Bingo Palace at Akwesasne. We visited with my sister and brother-in-law at

Flanders Inn in Massena, NY. This is where the excursion group would stay each

night and then be shuttled each day to the reservation. My sister told me how she would advertise,

charter the bus and would get the group together. The Reservation was the

closest gambling opportunities at the time. People would come to Akwesasne from

Rochester and Syracuse, NY and Ottawa, Ontario as well as other locations in

the region. At times gun fire would

erupt and busses were fired upon. Not everyone on both sides of the reservation

embraced the new gambling on the one US side. Being connected to these events

in so many different ways, the fact that different cultures were involved, and

the historic significance of the event all piqued my historical curiosity. The separation of the Mohawks of Akwesasne

begins in a practical way beginning in the Nineteenth Century. Their reservation

was “legally” divided after the War of 1812 because of the Jay Treaty. The

Mohawks still suffer from being divided by two national governments and three

provincial/state governments. Tribal governmental systems are imposed on either

side of the border by the paternalistic United States and Canadian governments.

This imposition has divided the Mohawks of Akwesasne by more than just the St.

Lawrence River but by borders imposed upon them. This book is a reflection of what occurred

in 1989 -1990 at Akwesasne and the history that propelled those events. It

starts with Mrs. Annie Garrow walking down the road

about two miles from her house on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River to Hogansburg, NY. A trip she had made many times. She was

carrying some baskets to sell. Her walk never took her off the reservation, she

didn’t have to cross the river. But she crossed a border that was imposed upon

the Mohawks. It would lead to a US Supreme court and start a situation that

eventually leads to the 1989-1990 uprising the Mohawks found themselves in. Some have said

that this was just a Mohawk Civil War, others have said that it was a squabble

amongst the Mohawks over who was making money and who was controlling it. The

book proposes that a system that was imposed on the Mohawks failed. If the

Natives had their traditional government or at the very least a unified

government that governed the entire territory,

I predict this would never have escalated to the point of destruction and death.

However, with the territory divided, two different governments and five

administrative districts enforcing laws, the outcome was violence. In general, no race, creed. or color has

been more oppressed or had genocide committed against them as the Native American

of the Americas. From the 15th century to the 18th

century 95% of the Native population was exterminated. Scholarly estimates of

Native American population loss are as high as 100 million. Where did they go?

They didn’t move, they were killed by disease (at times intentionally spread),

enslaved and worked to death by the European invaders, or just killed as one

would kill a bothersome coy-dog. The Natives that were left were coerced into

leaving their land. This was typically accomplished through promises in

treaties, none of which were eventually kept. In the case of Akwesasne, treaties imposed a border that

wasn’t there. Are there different interpretations of the

cause of the uprising in 1989 -1990, of course? However, as Robert A. Rosentstone tells us in his book, History of Film, Film on History, "No matter how much research

we do, no matter how many archives we visit, no matter how objective we try to

be, the past will never come to us in a single version of the

truth."Â That is certainly true of this uprising at Akwesasne. The

research that went into deciphering the history of the 1989-1990 uprising and

placing it in a chronological order can be found in the appendix. ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis work’s genesis is my doctoral

dissertation Clash of Cultures: Uprising

at Akwesasne. There are a number of individuals I want to thank for their

critique of my dissertation and therefore the creation of this book. My wife

and partner Keli (Keli Rugenstein, Ph.D.) is the

first I would like to thank. She has read and reread this manuscript numerous

times and put up with my late nights as I wrote both the dissertation and the

reworking of it into this document. Without her support, I doubt I would have

been able to finish. I would further like to thank those who were

instrumental in the creation of this work, offering input and suggestions. They

include Professor Dan S. White, Ph.D. of

the University at Albany, SUNY, Patricia West-McKay Ph.D. who is Co-Director of

the Center for Applied Historical Research at the University at Albany, SUNY

and who is also Director of the Martin van Buren National Historic Site of the

National Park Service. Dr. Arlene Sacks, Ed.D., Chair of my Doctoral Committee

and Director of the Graduate Programs at the Florida campus Of Union Institute and University (The Union Institute), was similarly a

contributor to the book. Others who have read over the manuscript

and have offered feedback include Charles (Chaz) Kader and Doug George-Kanentiio both from Akwesasne. A thank you goes out to Stephen

R. Walker Designs for his help with my book cover. Finally, I want to thank my

sons Don and Ernest Kristoph who gave up time with

their Dad so that he could do research and write. INTRODUCTION:What Uprising, Where? Akwesasne? During 1989 and 1990 there was an uprising

at Akwesasne (the St. Regis Indian Reservation) near Massena, New York and

Cornwall, Ontario. The event was marked by violence and death, with large

amounts of property and infrastructure destroyed or damaged, and families and

friends torn apart. Others who were

involved went to prison, were fined, or went into self-imposed exile to escape

the pressures of the aftermath. (Figure 1. Map of Akwesasne and the

Surrounding Area. Page 113) The reservation sits on both sides of the

St. Lawrence River. Approximately two-thirds of the reservation lies on the US

side of the border and one-third on the Canadian side.[1]

Akwesasne is located in part of two counties of New York State and two Canadian

provinces and interacts with five different jurisdictional governments. The

indigenous Mohawk culture is surrounded by and interacts with five larger

cultures: the French Canadian, the English Canadian, northern New York (along the St. Lawrence River) and the cultures

of both federal governments. Akwesasne has two independent, elected tribal

councils that govern the Canadian and American sides respectively. There are two generally accepted theories

why the uprising occurred. One theory is that the problems of 1989 and 1990

were a continuation of an ongoing feud between the Mohawks and the US and

Canadian federal governments. This feud

centered upon the issue of Mohawk sovereignty, the right of free and easy

access across the border, control of their land, and the ability not to be

charged duties or taxes for crossing the border.[2]

Other sharp controversies arose from time to time, but these were the issues

that caused the most friction. However, there are a few differences between the

uprising at Akwesasne and the other government interactions of the past. In this uprising, traditional friends and

cohorts were split down non-traditional party lines. Not only were there splits

among historic allies; previously opposing sides on all other issues formed an

alliance on this one. The major

differences in the 1989 through 1990 uprising were the loss of lives at

Akwesasne, and later at Kanesatake, (near Oka),

Canada and the lawlessness and violence that occurred. The other accepted theory for the violence

at Akwesasne is it was a civil war over the issue of gambling, much like the US

Civil War involved the issue of slavery. The situation was exacerbated by the

response of the state, provincial, and federal governments involved, and their

initial reluctance to get ensnared in the situation. There

is a yet an unexplored theory for the conflict and violence. The historical record indicates

increasing conflict between the various cultures at Akwesasne since the 1950s. This intensified in 1989 and reached a peak in

mid-1990. During 1989, the Canadian government, the provinces of Ontario and

Québec, the US federal government, and New York State ignored requests from the

elected Canadian and American tribal governments for assistance. Despite this,

the elected tribal governments were still encumbered by the rules and regulations

of their respective federal governments and jurisdictional considerations. The

external cultural and jurisdictional restraints prevented the tribal

governments to combine to settle the problems that developed at Akwesasne

during this time. By 1990, the various governments realized

the seriousness of the situation but the one authority that had the greatest

ability to act, New York State, did not do so until after the loss of

life. The weight of this prolonged cultural conflict on Mohawk society

was evidenced by the destruction of infrastructure and the blockading of roads

and death. When examining the events at Akwesasne psychologically, the

situational stress of the situation caused people to act out and became violent. As the stress and

anxiety increased people acted violently. This scenario created stress resulted

in the Mohawks acting out in a predictable manner, striking out at others. As

the various systems involved broke down, stress and anxiety increased through

all of the systems. CHAPTER 1Understanding the Politics and Institutions at AkwesasneTo understand the situation at Akwesasne,

it is important to review and understand the various jurisdictions and

institutions that are encountered on the reservation. These institutions include

various governmental, police and investigative agencies with their associated

federal, provincial or state and tribal jurisdictions. Examining the Government

at Akwesasne, includes an assessment of the Longhouse/ Traditionalist

government, the Canadian Mohawk government, the American Mohawk government, and

the Warriors. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the relationship

between the United States federal government and Akwesasne and between the

Canadian federal government and Akwesasne. Akwesasne is surrounded and divided by two

federal jurisdictions: The United States and Canada. Additionally, the

reservation must contend with the governments of New York State and the

provinces of Ontario and Québec.[3]

Residents of the reservation have three area codes: 613 that covers Southeast

Ontario, 514 covering Southwest Québec, and 518 covering Northeast New

York. Each serves a different portion of

the reservation. This division is echoed by zip codes; the American side’s zip

code is 13655 and the Canadian side is H0M 1A0. The

population of this multi-jurisdictional community is about 13,000 people.[4] Because of this unique situation, school

students are also affected. Some children from the US side of the border go to

Canadian schools, and all or some Canadian children go to US Head Start

programs.[5] There are three competing self-governments

on the reservation loyal followings; the Canadian Mohawk Council of Akwesasne,

the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Council, and the Longhouse Mohawk Nation. Traditionalists from both sides of the

reservation follow the rituals and traditions of the Longhouse government

however the federal, state, and provincial governments do not officially

recognize the Longhouse government. The St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Council

oversees “funding programs from Washington and Albany” and interacts with the

US side of the reservation.[6]

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne connects with Ottawa for Canadian programs and

agendas. Each recognized council has its band (membership) lists for its

community. Technically, residents of the reservation cannot vote for both councils,

however, there is nothing to stop a resident from one side of the reservation

from moving from one voting roll to the other.[7] [1] James Bell, Implementation of Promoting Safe and Stable Families by American Indian

Tribes Final Report – Volume II Case Study Reports (Arlington, VA: James

Bell Associates, Inc., 2004), 153. The Canadian side of the reservation

extends for 7,400 acres and on the American side of the border the reservation

covers 14,648 acres. [2] “Sovereignty is the claim

to be the ultimate political authority, subject to no higher power as regards

the making and enforcing of political decisions . . . Sovereignty should not be

confused with freedom of action: sovereign actors may find themselves exercising

freedom of decision within circumstances that are highly constrained by

relations of unequal power.” The Concise

Oxford Dictionary of Politics, s.v.

“Sovereignty.” [3] Michael T. Kaufman, "To the

Mohawk Nation, Boundaries Do Not Exist," The New York Times, April 13, 1984. [4] Russel Roundpoint, "Akwesasne, Ca.,” Mohawk Council of

Akwesasne, http://www.akwesasne.ca/ (accessed

September 10, 2007). [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. |